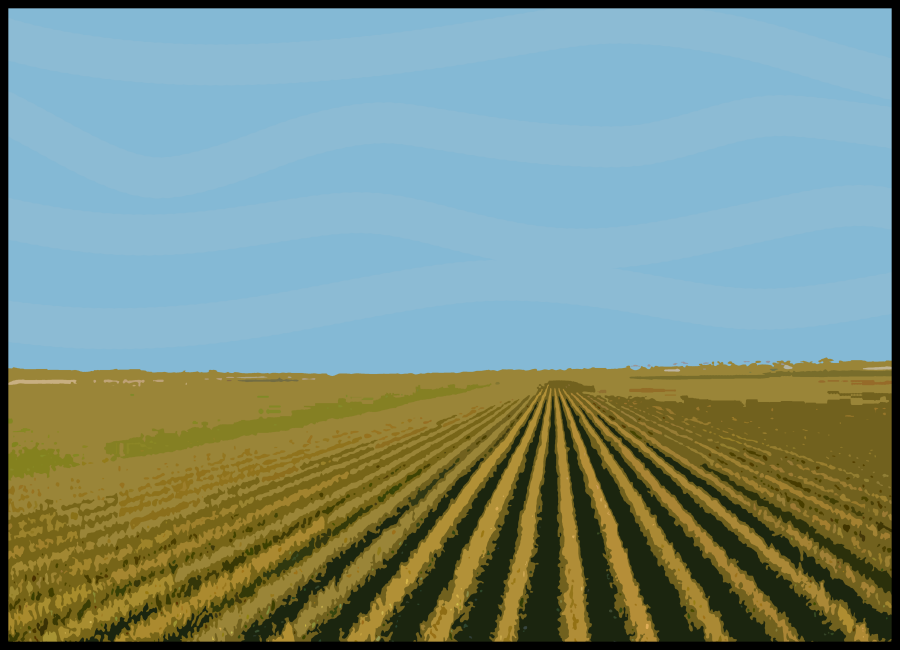

Graphic by Jordan Lee.

We’re getting into late fall, which means carpooling to pumpkin patches, Instagram posts about the brightly colored Slough path, and dealing with your neighbors keeping their rotten pumpkins around for way too long. But as much as we love the harvest season aesthetic with its hay bales and apple picking, we can’t ignore the communities who create it every year.

It isn’t a bad thing that students want to get into the spirit of things in the fall. In 2020, it’s more important than ever that we hold on to the hallmarks of normal life, albeit in a more socially distanced way.

Heading off campus to get some fresh air, buy a caramel apple, and walk around in a wide-open space is a perfectly understandable desire when you spend all your free time inside with the same few people.

This agricultural tourism, as students take photos with scarecrows and throw leaves up in the air for the perfect Instagram post, isn’t harmful to farmers, either. Small farms, especially family farms who sell directly to communities, have been hit hard by the pandemic. Even if they look a little bit different, they’re still small businesses.

But when Augustana students return from the pumpkin patches and corn mazes, they’re back to criticizing rural communities for their high COVID-19 numbers and differing political views.

You can’t separate the fall aesthetic from the communities it stems from. The farmers we criticize for not being smart enough, savvy enough, or modern enough for our tastes are the same ones who get food to our plexiglass-separated tables in the CSL. You can’t call a person a hick one day and then consume the products of their labor the next.

It’s hard to see that at Augustana, an institution largely made up of students from the Chicago suburbs and hotspots around the Midwest. However, it’s easier said than done to increase an entire demographic at a college.

“They say it takes three years of consistent infiltration of a certain area to get any momentum,” Courtney Wallace, Chicago region director of Admissions, said. “Every part of our country has a different culture. There’s certain parts of states and certain cities where kids often leave their region. But there’s places where many students don’t leave the state to go to college.”

Consequently, it’s hard to pull in new prospective students from an area without a strong alumni network to get the word out. Convincing students to come to a college they’d never heard of before is one thing. Convincing students to attend a college with a large sticker price and the “liberal arts” label is another.

“Oftentimes the social narrative and media narrative of higher education makes people think places like us, and even places that are much easier to get into and much less expensive, are just out of reach for families in rural communities even though they’re really not,” Mike Pettis, associate director of admissions for strategic initiatives and data analysis, said.

It’s difficult to reach new areas in the pandemic, meaning that fewer small town prospective students will look into Augustana. Pettis and other Admissions staff hope to combat this by trying new strategies, like Zoom panels with current students to chat with high school students, but participation in those events depends on the prospective students themselves, keeping numbers down.

“I’ve counted the people I have met from Iowa and it is, I think less than five. I think four,” John Flannery, first-year, said. Flannery came to Augustana from Washington, Iowa, after his older sister enrolled the year before.

Despite Augustana functioning as its own little community, it only goes so far to emulate the experience of growing up in one. “Everyone knew everyone,” Flannery said. “That’s the blanket statement that everyone says but with a town of like 6-7,000 it’s kind of true. You know of everyone, you see the people working at the grocery stores, you know people’s faces.”

That familiarity drives the interpersonal understanding that makes small towns thrive. However, the positive attributes small towns in America are known for often stem from the same issues that make them difficult to stay in.

When a community rallies around a cause, helping a family through hardship or keeping a business alive, it’s a sign that they don’t have the government support necessary to hold up people in need.

I saw that often growing up in Milton, Wisconsin. As a teenager, I went around my neighborhood every Halloween collecting canned food and hygiene products for the food pantry. I had friends who babysat at low rates for neighbors who worked when their children were finished with school in the afternoon. When I closed at work, my mom and sister would often be out of the house, volunteering with our parish and the local men’s shelter.

It’s heartwarming but the implications are disturbing. When your community is surrounded by woods and farmland, it can feel like you’re separated from the rest of the world.

“That’s just something that I’ve always just been raised to do,” Flannery said. “Always raised to go to the local restaurants, not buy all these super commercialized things. Just always support the community. I feel like in general, that’s a great thing to be mindful of.”

The independence bred by being self-sustaining has its fallbacks. And they’ve been more apparent than ever during the pandemic. Despite a mask mandate, people are hesitant to believe a government who habitually ignores their needs. Investing in interstate construction around a town is a very different ballgame from investing in the social support needed to make that community flourish.

To turn that lack of support around and blame the community itself for its issues is all too easy. Calling rural Americans uneducated for joining the workforce rather than attending college doesn’t sit well when the local school district is chronically underfunded. An area’s low median income means fewer students can get the educational support to get into college, much less afford it.

That lower income stems from a lack of incentive for businesses to invest in a community, and money slows to a trickle when “Big Agriculture” suddenly has a lower need for crops due to a pandemic. Farmers depend on government support, and, finding that the majority of coronavirus stimulus payments went to corporate farms, lose faith in the support systems meant to protect them from economic fallout.

“Our high school had FFA, which is Future Farmers of America. I was never a part of that even though everyone I knew was,” Hallie Weis, an out-of-state first-year from Wisconsin, said. “Agriculture is a big deal. Education is a big deal because a lot of teacher’s kids go to that school district.”

The needs of the community and the people who have them are intrinsically tied together. As a result, the people in small towns know how to take care of each other. “The mayor of Washington was the owner of a bar and grill,” Flannery said. “So that was just one of those fun things where you could talk to him about Washington while getting a beer and a sandwich.”

When the lines are blurred between people’s jobs and their lives as community members, a community thrives. It becomes difficult to leave that community come adulthood, which feeds into low enrollment rates for out-of-state colleges.

“Many students don’t leave the state of Iowa to go to college. And that’s exactly the opposite in Illinois,” Wallace said.

Pettis, who has been working to increase the number of students enrolled from Minnesota and Wisconsin, echoed Wallace’s sentiment. “Trying to convince students in Wisconsin to leave is very difficult, just because of the sheer size of the state-run public system,” he said.

Weis, who felt the pressure to attend University of Wisconsin (UW) Madison, saw how the UW system impacted college enrollment at her high school. “That’s where people assume you’re going,” she said. “Most of the people from my high school stayed in Wisconsin and some went really far away.”

Since Augie differs from large, state-run institutions, it creates its own community despite the largely suburban student body. “I feel like Augustana’s kind of like this community almost, or a small town. It does feel like home. It definitely feels like it’s just a community for everyone,” Flannery said.

While the “Augie bubble” has its upsides, it often lacks the energy of a real small town. Students tend to fend for themselves on campus, focusing on their own academics and extracurriculars rather than working to help the community around them.

“You ought to be able to put aside some of those concerns so you can focus for those four years,” Jason Peters said of college students forgoing communal responsibilities. Peters is an English professor on campus and teaches Environmental Literature as well as having founded Augie Acres. “But we can’t keep acting as if being incompetent of basic human tasks is okay, and I think liberal arts colleges sometimes do that.”

While college students are expected to be enterprising and have new experiences at school, they often don’t invest their time and energy in making their community a better, more helpful place. The empty boxes in the Brew asking for clothing donations and the sparse contribution to Campus Cupboard demonstrate that. Even Augie Acres, the community garden run by the Augustana Local Agriculture Society, has struggled to find purchase in the campus community.

“I think, because of the majority suburbanite perspective, we are not a very environmentally conscious campus,” Peters said. “That’s not a part of our culture the way it is at other schools. Maybe we have it a little bit on the faculty, but I don’t think the students who come here, I don’t think it’s a part of their equipment.”

While Flannery has found that Augustana has communal ideals, it still lacks some of his hometown’s values. “The fact that our communities are self-sustaining makes a community better as a whole. A lot of the more urban cities, it’s more individual as opposed to, you know, supporting the community,” he said.

Augustana’s campus, as COVID-19 has necessitated an increase in single-use plastics on campus, has struggled to remain environmentally conscious during the pandemic. As a smaller school, however, Augustana has the ability to take on some of those small town practices and work to increase sustainability on campus.

“I’d like to see a better volunteer culture around here, especially outdoor volunteering. It would be simple to give students jobs to take care of the campus,” Peters said. Augustana is well-suited to incorporate the positive attributes of rural areas in the United States, and in doing so, unpack the negative attributes of close-knit communities as well.

Small towns aren’t perfect. They’re not ubiquitous either and each one has its own problems. However, alienating those areas for their issues and sidelining their needs only exacerbates them by not letting them enter the conversation.

Augustana College is a liberal arts institution and prides itself giving students an education that stretches far beyond their chosen field. A vital part of that education, as we near an election and struggle under an ever-worsening pandemic, is teaching students the value of their role not only as a student, but as a member of our community.

Additional reporting by Kaitlin Jacobson

Fall at Augie highlights problems on and off campus

October 31, 2020

View Comments (2)

More to Discover

Jack Brandt • Nov 2, 2020 at 8:31 am

Hi John! Hi Hallie! As a suburbanite, this was really eye-opening. I never really thought this way about my place in a community before.

Lori Neubauer • Nov 1, 2020 at 11:55 pm

Well done! As an Augie parent, you want your child to attend school somewhere where they feel they belong and can make a difference. Augie is doing that across its campus!