Special collections records absent in discussion of labor rights

May 13, 2022

Every day of the week, millions and millions of people clock in and out of work. The United States relies on every type of job under the sun to keep the gears of life turning and moving forward. On a local level, Augustana is no exception.

Students can be found as employees in many different offices, from working in admissions to serving food in the dining hall to organizing events that the college provides for the campus. A large portion of students find themselves clocking in to a campus job, including myself and virtually all of my friends. So why aren’t there any records of us talking about it?

To write an article about the history of labor at Augustana, I took a trip down to Special Collections on the first floor of the library.

I met with a Special Collections worker and he handed me two manilla folders, a thicker one filled with labor relations in the Quad Cities as a whole and a very thin one with information about labor practices on campus.

There were less than five sheets of paper in the Augustana folder. This surprised me, since so many students rely on income from campus jobs, potentially alongside another off-campus job, to make ends meet while trying to cover the mounting costs created by college.

As I opened the thin manilla folder in the quiet Special Collections room, several email printouts spilled onto the table. They were all sent to faculty and staff detailing student hiring and employment practices dated 2019.

One of them detailed how, in the first week of classes, 106 students workers reported working over their hour limit at the college. Faculty and staff were then reminded that international students are limited to 20 hours of work weekly per job position, and domestic students are limited to 10.

Other emails served as general reminders for employment practices going into the new year.

At the beginning of the folder was a paper from 2013 explaining student worker guidelines, which discussed ways to avoid nepotism by not allowing students to work in the same department as a close family member. Generally, not a lot of new information was brought to the table in this folder.

After reviewing these documents, I began to sift through the larger stack of newspaper clippings discussing labor in the Quad Cities.

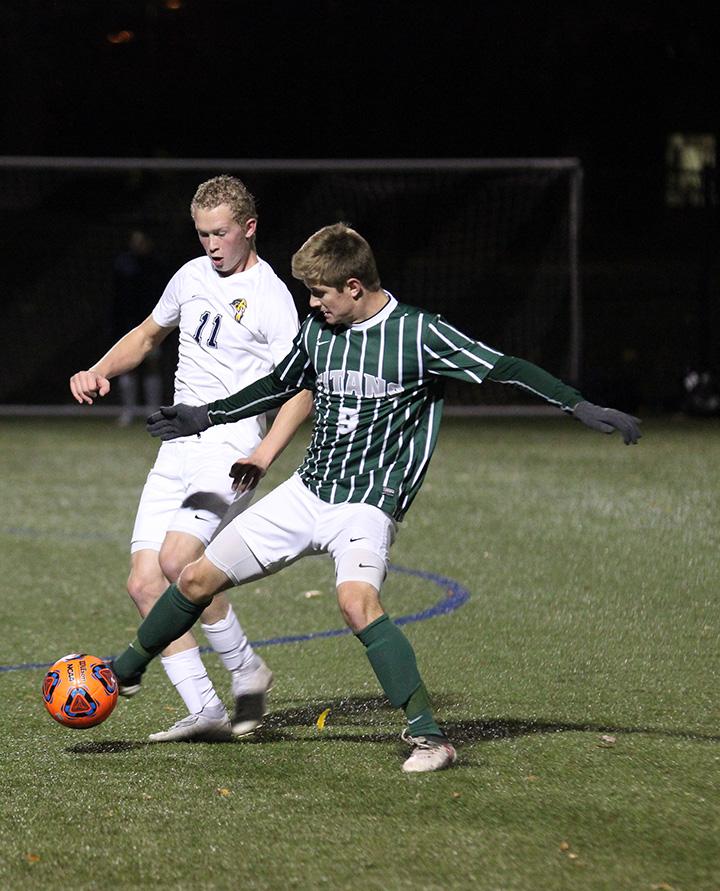

Tales were spun of David facing Goliath in the form of protests and walkouts being held for employees to make a change in large companies.

This was the first sign of recurring labor issues in the area. People who were in the Quad Cities area in 2021 likely remember the John Deere strike that began this past October and ended in November.

The United Automobile Workers (UAW) union walked out on the company to protest the rejection of one of their contract proposals.

But this fight by the UAW has continually happened again and again, with one of the earliest newspaper clippings in the Quad Cities dating back to 1948 when the UAW wanted to take over the Farm Equipment union.

This constant fight for labor rights over many years can be seen in the Quad Cities and actually mirrors the call for higher wages on Augustana’s campus. Buried in the stacks of labor strikes was an article titled, “Augie battling payroll squeeze” by Kerry Schmidt for the Daily Dispatch (now the Dispatch-Argus), dated March 4, 1979.

It discusses how, after the Illinois Minimum Wage Act was amended in 1976, Augustana never complied with the wage raise for students. As a result, the state was calling for Augie, among other colleges, to pay student workers back for the wages they should have earned but did not receive from not meeting the minimum wage.

This means that in 1977, the minimum wage was raised to $2.20, but because of an exemption to the 1971 Minimum Wage Act, universities only had to pay 85% of minimum wage.

This meant that students at Augustana were being paid 24 cents less, working at $1.95 an hour.

The reaction from Augie was less than enthusiastic toward the call from the state to pay the wage differences, which would have amounted to over $45,000 in 1979.

Adjusted for inflation, that’s roughly $175,800 by today’s standards.

In the article from Schmidt, a quote from Glen Brolander, who at the time served as Augustana’s vice president for financial affairs, claimed that “the state is acting ‘unfairly’ with private colleges,” regarding the pay raise. Schmidt ended the article by stating that Augie, among other colleges, was protesting the need to pay back wages.

This battle sounds all too familiar to current student workers on campus. As I looked back on Observer issues from previous years, the battle to meet minimum wage has been present for my entire time on campus. On Jan. 1, 2020, the minimum wage was raised to $9.25 and the college has since met this marker.

However, minimum wage currently stands at $12.00 per hour in Illinois and is set to rise to $15.00 an hour by 2025, and college wages still sit at $9.25. This was covered in an article in the Observer in 2019 by Melida Castro.

As minimum wage continues to elevate, the strain will be felt increasingly by students. The topic of pay has and likely always will be frequently discussed by students, and yet there is very little to be found in the records about the topic.