Students play a key role in their professors’ tenure process

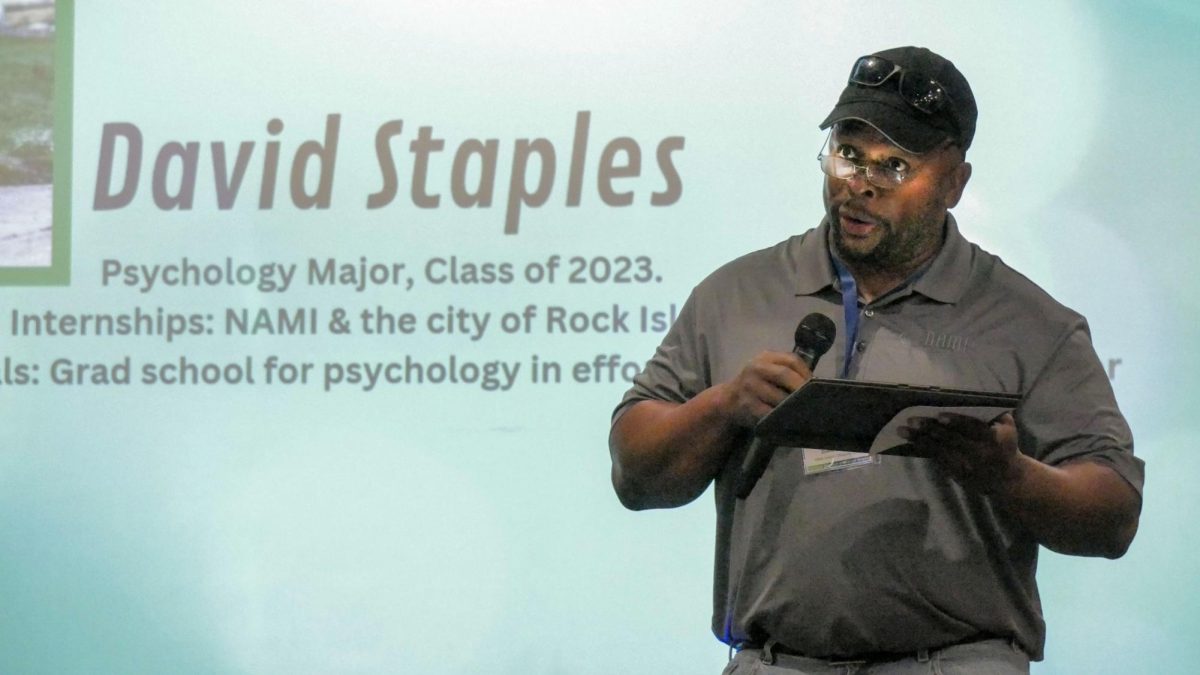

Tenured Dr. Austin Williamson presents on universal emotions on March 8 at Evald room 314.

May 13, 2022

Augustana currently prides itself on having 116 tenured faculty members in its collection of 197 full-time faculty.

Tenure is a complicated and multilayered process where faculty members are assessed for permanent teaching positions. Many people are involved in the tenure process, including the candidate, their department chair, colleagues and the students. However, the primary group in charge of evaluations for tenure-track and non-tenured faculty is the Faculty Welfare Committee (FWC). The FWC is currently composed of six division chairs, and each division chair is elected to their position by the faculty members of their division.

Dr. Umme Al-wazedi, associate professor of English and FWC chair, describes tenure as “a rigorous review process through which a faculty becomes permanent.”

When tenure-track faculty members are first hired, they are hired as non-tenured assistant professors. That faculty member then goes through a series of regular reviews. Every two years, there is a major review from the FWC (two-year, four-year and six-year). After six years, the FWC, provost and president make the final tenuring decision for that candidate.

“After every review, they get a letter from the Faculty Welfare Committee. These letters are considered as feedback about how they are progressing towards tenure,” Al-wazedi said.

The department also writes letters every two years. The first two letters may include the candidate’s progress and colleagues’ classroom observations, and for the third letter in the sixth year, all colleagues in the candidate’s department weigh in regarding the candidate’s status in the department.

Although the FWC is primarily in charge of the tenure evaluation process, they are not the only ones responsible for the final decision to grant tenure. The provost attends all reviews and gives feedback, and the final hearing is also attended by the president of the college.

Once tenure is granted, it lasts for life (except in specific rule-breaking instances), so this system relies on many checks and balances to make the process as fair and non-arbitrary as possible.

One of these checks is built into the records candidates collect. To prepare for their evaluations, candidates must continuously compile materials such as past assignments, rubrics and samples of class work.

“The candidate writes a narrative reflecting on their teaching, advising, service to the college, their scholarship and often their community work,” Al-wazedi said. “For each of these sections, they provide examples of how they have been able to achieve their goals and the goals that are set by their department or program.”

Dr. Austin Williamson, associate professor of psychology and neuroscience, received tenure last year and said that each of these sections are considered, but one in particular stands out.

“You do talk about your scholarship and your service to the college as well, but because of our orientation as a small liberal arts college, the teaching really takes the center stage,” Williamson said.

Students contribute to the tenure process by submitting anonymous IDEA forms at the end of each term. These forms contribute to the status of the candidate’s progress every year. However, these forms can contain some inherent biases.

“The Faculty Welfare Committee is aware that these are not perfect tools because often students also let their perceptions of race, gender, language, ability etc. affect their responses. Either in a positive sense or in a negative sense,” Al-wazedi said. As a result, IDEA forms are balanced with other candidate materials.

For the final tenure hearing, additional student voices are considered. The candidate will typically select 10 to 15 students who have taken their classes to take a survey about the candidate’s merits. However, this is once again balanced with at least five other students chosen randomly from the candidate’s past class lists.

Williamson selected students who spent a lot of time working with him, particularly through research.

“Some of the students I gave as possibilities were recent alumns as well,” Williamson said. “Because by the time that process comes up, sometimes the students who have done research for a year or more have graduated, so it’s good to have those people as a possibility.”

Dr. Meg Kunde, associate professor of communication studies who was tenured last year, focused on selecting students who could offer a range of perspectives on her teaching.

“I tried to do a mix of people who were my advisees and who weren’t my advisees, who were comm majors and who weren’t comm majors,” Kunde said. “I thought it was important that just because I’m in the comm department, that shouldn’t mean that I just facilitate comm people learning.”

The tenure process is extensive, and it demands a lot of time and effort from all parties involved.

“At Augustana, I think the way that it plays out most frequently is that it kind of separates your time into this very intensive developmental period, where you’re both getting a lot of oversight and a lot of guidance… [after receiving tenure] then that level of oversight and guidance gets to be less,” Williamson said.

When a faculty member is granted tenure, they are generally expected to spend more time serving on committees. This title also comes with increased academic freedom and job security.

“Once you get tenure, the idea would be you’re more likely to speak up against things, perhaps in your institution, that you think could make change for the better. Or you don’t have to be afraid of experimenting in your class, which could produce really innovative results,” Kunde said. “You have more freedom to explore topics and to experiment in your classes.”

The tenure system of higher education generally results in a few employment differences between faculty on tenure track and those not on tenure track. The evaluation process is also separate between tenure track and non-tenure-track faculty.

According to Kunde, there’s a difference in academic freedom, stability, oftentimes compensation and sometimes opportunities between tenure track and non-tenure track teachers.

“There are so many wonderful, quality colleagues I have who aren’t on tenure track. It’s hard, because when you’re not on tenure track, you don’t have job stability,” Kunde said.

Faculty members on tenure track at Augustana are evaluated extensively before they are granted their position. Augustana has been diligent in ensuring each step of the tenure process is as balanced and thorough as possible. This emphasis is not something that FWC chair Al-wazedi takes lightly.

“I was an international student. In my country and many countries in south Asia— I would say all— there is no student evaluation. There is no check and balance,” Al-wazedi said. “Teaching is a two-way street in America. But in my country it’s one way: it’s delivered to you. Whereas here, you contribute.”