Native American conservation

May 17, 2023

It has long been argued that Native Americans are the first environmentalists. The coexistence between the natural world and the spirit world, and the interconnectedness between the two resulted in a deep respect for nature and a long-lasting journey to maintain it.

Native Americans, such as the Wisconsin-based Ho-Chunk nation, have made tremendous strides in land conservation over the years, solidifying its importance and strengthening their cultural ties to the environment.

Despite this, they have not remained outside of modernist developmental activities, with urban expansion, vehicles and individual decisions having an impact on lands under their domain.

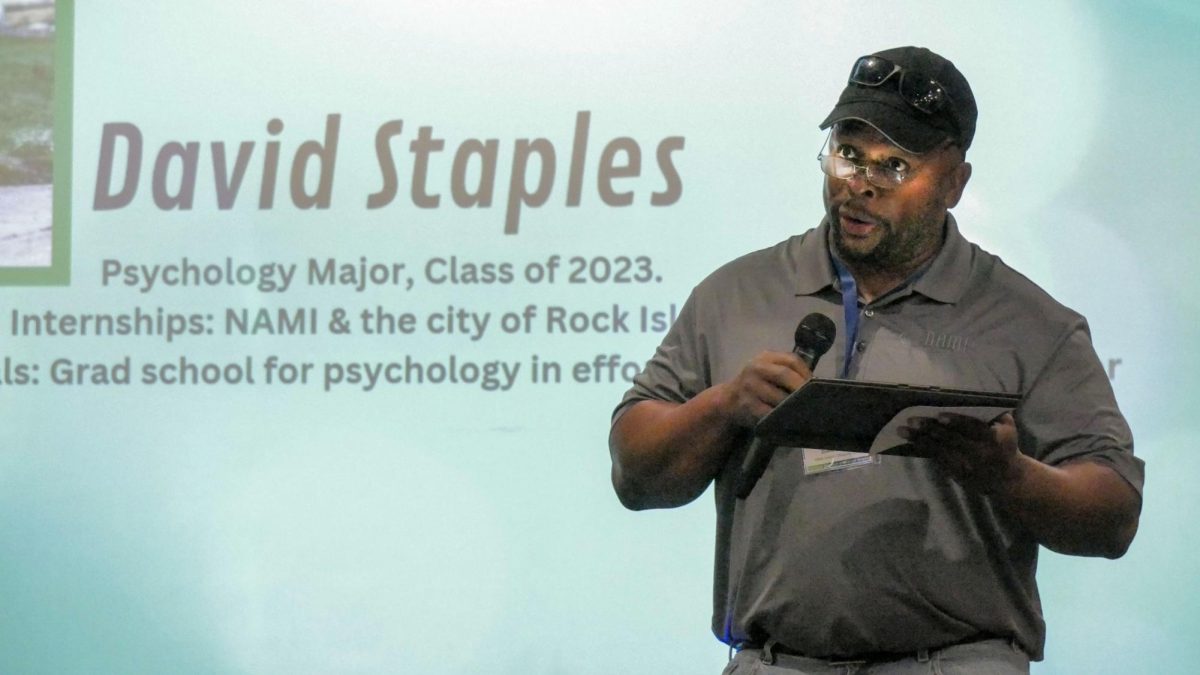

Tina Brown, the executive director of the Department of Natural Resources of the Ho-Chunk tribe, said “Our homes, vehicles, enterprises, and our individual decisions on a daily basis impact our environment. We are not immune to progress, modernization, and capitalist activities that influence our environment.”

Yet, compared to others, their conservation efforts still offer much for us to learn, with a clear focus on lessening their negative ecological footprint, rooted in a belief that harming those in systems they are interdependent with, the land, water and air, harms themselves as well.

This interdependence is something that we should recognize ourselves. Our transportation, what we eat and drink, it all ultimately originates in the same place, our planet, and we do depend on it to an extent, so we should value and act to conserve all that it has to offer.

“What differentiates us from non-indigenous peoples is our traditional ecological knowledge that is passed down from our ancestors, which taught us we are part of the natural world. And it is here for us to use and care for responsibly because we are interdependent with all of the living systems here: water, land, creatures of the air, creatures on the earth, and creatures in the water. We cannot harm them without harming ourselves,” Brown said.

Again, this interconnectedness between beings and respect for the planet is striking when compared to efforts taken at the state, or even federal level, which arguably tend to favor capitalization and economic gain over environmental preservation.

As strides to develop alternatives to fossil fuel are slow and non-recyclable materials continue to build up in landfills, questions are raised as to what we aim for in the future of our environment – with issues on our economy, and our economic benefits taking precedence over environmental damage and loss, but soon there will be nothing more to lose.

A focus on individualism, in the emphasis on an individual’s intrinsic needs and wants, is a stark contrast from the ideologies relating to ecology and interconnectedness, and consideration for nature resources abided by in Native American land conservation.

Similarly within their consideration is the future, as knowledge of land preservation is passed down, and actions are taken to ensure the land is there for

generations to come.

These issues did not develop overnight. They were the result of damage we inflicted over time, making the selfless mission of the Ho-Chunk tribe to preserve the environment all the more important. This sentiment was echoed by Brown.

“For many Indigenous nations, we are not taking care of the earth and the life upon it for ourselves; we are taking care of it for our children, their children, and the future generations to come,” Brown said.

As we note the sacrifices of those before us and prepare for those soon to come, it’s important to consider if what we have lost is worth the reward. We are relatively economically stable and have access to a myriad of resources, but what of our environmental future?

I think it is clear that the values of the Ho-Chunk that extend beyond multiple generations are something we can learn from. Responsibility, in particular, is a key component that should be addressed in the environmental steps taken outside of indigenous lands.

The steps taken now will impact future generations, reinforcing environmental accountability and the need for action, particularly in the realm of land conservation.

While this is a change that should occur within our non-indigenous environmental landscape, Brown says that she would like to reform tribal laws to ensure that they coincide with pre-existing ecological knowledge.

“We need to push forward in exercising our tribal sovereignty and make necessary changes to our Ho-Chunk Nation Constitution,” Brown said.

Including language that speaks to the ‘Rights of Nature’ language provides those within the Ho-Chunk nation with an emotional connection to the natural world, as they consider not only their rights as people, but how these rights relate to nature as a whole.

“We too need to put down our cell phones, turn off the TV and computers

long enough to devise our individual and tribal paths of accountability, and make our sacrifices for the sake of all humanity, walking the environmentally dutiful footsteps of our ancestors,” Brown said.

The urgency to blend the modern with the traditional falls in line with the multigenerational environmental preservation that characterizes not just the Ho-Chunk, but many other indigenous tribes, as they adapt their prior knowledge and long-lasting beliefs to coincide with the evolution of environmentalism.

Considering the environment, not as a stagnant, voiceless entity from which we

can reap benefits without any regard for its well-being and effects, is something that we need to move beyond, following in the footsteps of the first environmentalists and bridging our generational gaps in environmental preservation.