The Grammys are a terrible attempt to objectively judge subjectivity

April 16, 2022

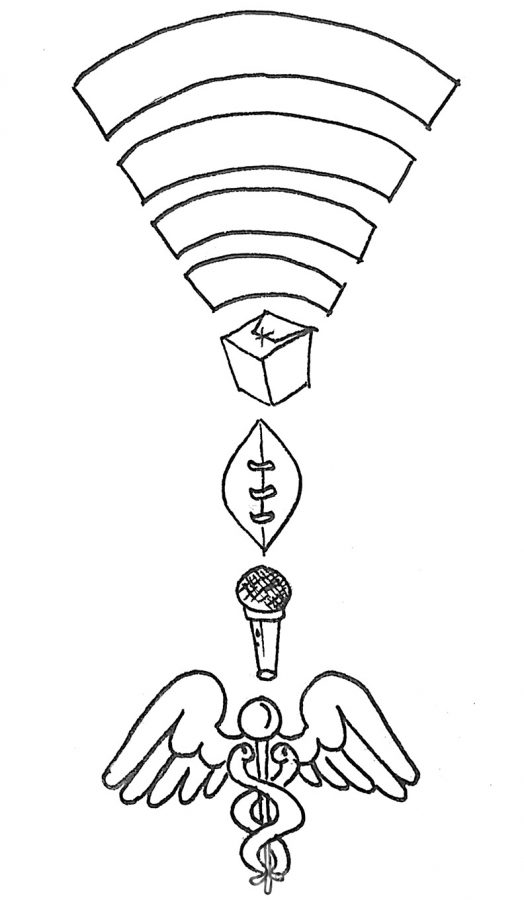

With the 2022 Grammy Awards finally behind us after it was initially postponed in January due to concerns with the COVID-19 Omicron variant, it is the time of year for people to evaluate whether the Grammys truly matter when considering the sheer presence of music in the mainstream.

We are heavily invested in it, whether it be having our earbuds in while walking to class or having music as background noise for studying. Music, at its core, is a very subjective field where everyone’s so-called ‘taste’ will vary. While genres like rap have dominated pop music and streaming platforms in the past decade, some individuals could prefer different genres like rock, for instance.

The Grammy’s can also be viewed as elitist, as Amanda Petrusich of The New Yorker writes following the recent ceremony that the occasion is “just an increasing awareness of the vast and devastating divide between the way some people live and the way most people live.”

This notion reflected words from the show’s host Trevor Noah, who advised to not “even think of it as an awards show;” rather, “this is a concert where we’re giving out awards.”

The awards that serve as the crux of the show have been questioned and critiqued throughout their history since 1959, where the Recording Academy’s lack of transparency behind their voting process has served as a controversial subject.

A recent peak of irritation came when The Weeknd, a three-time Grammy winner, was snubbed from the 2021 awards after his album After Hours received widespread critical acclaim and “Blinding Lights,” one of the most acclaimed and commercially successful singles of the past few years, received no nominations. Consequently, he boycotted the ceremony by no longer allowing his record label to submit his music for nomination.

In a 2020 video essay titled “The Best & Worst of Grammy Nominations (Album of the Year), music expert Alfo Media claims that the Grammys “nominate mediocre albums and snub great ones.” In his analysis, he observes the user and critic scores of Album of the Year nominations throughout the 2010s and evaluates whether the winners seemingly ‘deserved’ their awards.

Scores varied drastically from year-to-year. However, a common theme of his analysis was that several projects beloved by both fans and critics were not nominated, and they could have easily replaced albums that were on the ballot but not critically acclaimed.

If this doesn’t accentuate the subjectivity of how we perceive music and how the Grammys serve to propel their superstar darlings into the spotlight, I’m not sure what would.

Even though the Academy increased the number of nominees for the top four categories (Album/Record/Song of the Year and Best New Artist) from eight to ten to “make room for more music,” not everyone will be recognized if they don’t have a big enough name.

Race is another key factor to eye in this context. Yes, Jon Batiste just won Album of the Year at this most recent ceremony for We Are, but only 11 Black artists have won the most prestigious prize of the night in its history. Will we see more opportunities in the future? Only time will tell.

In the end, it is obvious that millions of viewers will tune into every Grammy or Oscar ceremony to see their favorite artists or actors vie for awards that ‘celebrate’ the music industry, but ‘favorites’ are exactly what they seem: subjective and very opinionated viewpoints toward what may sound ‘good’ or ‘bad.’