Trigger Warning: This article discusses eating disorders/disordered eating.

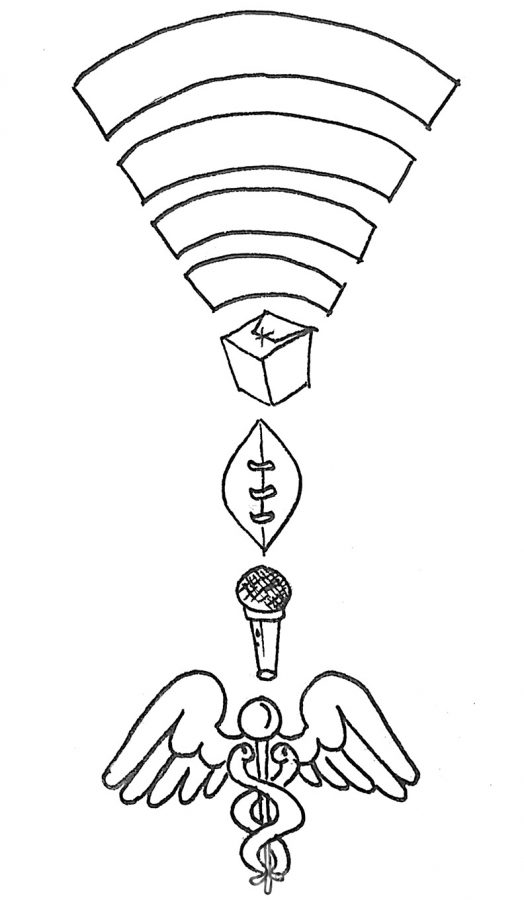

The pandemic has pushed college athletics as close to the breaking point as it can. Reducing crowds, limiting team bonding and encouraging improvements while college students grow more burnt out every day has whittled athletics down to the bare bones.

As minimal as they have been this school year (more so first semester), athletics still demands top performance from students. Despite Augustana being a DIII school with an attitude of putting mental health and academics first, the stress to compete and win still affects athletes.

Plenty of them turn to their sport when stressed. A good workout or a solid run can clear the mind and help the world make a little more sense.

But when your usual source of stress relief becomes a stressor, the relationship an athlete has with their sport becomes tenuous.

“My favorite thing is running. My least favorite thing is running,” Daniele London, senior, said.

It’s a double-edged sword, especially when the pressure to compete is one of the factors leading someone to seek a comfort mechanism. Toxic relationships to activities, especially athletics, create damaging cycles in which a participant seeks comfort in the same thing causing them stress.

Limiting a sport to solely competition changes the way athletes view it. It becomes a numbers game where loss is considered a personal failure. Not improving means that someone didn’t try hard enough, didn’t practice enough or didn’t do the right thing.

It’s often easier to blame yourself and your body. “In long-distance running, eating disorders or disordered eating are pretty prevalent.” Katie Johnston, sophomore, said. “You get on the line and you see the common bodies, the skinny, lean girls, so it’s hard not to compare yourself to others and be like, ‘This girl is fast but she’s really skinny, maybe if I get skinnier I can be faster.’”

Disordered eating and eating disorders are shockingly prevalent in college athletics. A University of Michigan study found that female college athletes are two to three times more likely to meet the criteria for an eating disorder than non-athletes.

The internalized pressure to have a body that can succeed drives people to put aside what they know to be healthy. Despite often knowing more about health and nutrition than other students, athletes are less likely to use that information for their own wellbeing.

With a strict exercise schedule and an ingrained sense of knowing the best things to fuel with, that sort of information doesn’t seem as applicable for someone who already seems to take care of themselves.

“There are some people that it’s very healthy in the way they’re eating enough and allowing themselves to splurge once in a while, but then there are people who have really unhealthy relationships with it and that’s when issues start,” London said.

Disregarding information about proper dieting leads to over-exercising and under-eating. That imbalance contributes to disordered eating in surprising ways. Someone with seemingly good nutrition may be eating well on paper, but in reality, they may harshly overcompensate by working off those calories.

When athletes feel like they’re on their own to take care of themselves, the issue grows.

Non-refereed sports like gymnastics, track and field or swim can feel more like a performance than an athletic competition.

While refereed sports like basketball or volleyball work to score against another team, sports in which a participant works towards a time or numerical goal displays an athlete in front of onlookers.

As a consequence, more attention is paid to the body. “It’s hard, I feel like there’s such an emphasis on this one type of body for women, and it’s the same in cross [country]. The skinny, lean body is emphasized,” Johnston said.

That emphasis is a major factor in how athletes begin to forge unhealthy relationships with diet and exercise.

“It’s hard because you’re eating a lot of food to fuel, so then you’re like ‘Is this going to change my body, what if I eat too much, and I get bigger, and I’m not the ideal body for running?’ So it’s a hard balance,” Johnston said.

Stress from athletes combines with the usual pressure to achieve a certain body type outside of the sport. While a sport trains you to be competitive, intense and strong, female athletes face a double standard where athletics contrasts the societal standards of demure and softer women.

“With guys running, you just want to look strong. With females, you want to be that small, skinny girl because that’s what the fast girls look like. But that’s not always true. I was at least 20 pounds lighter [in high school], but I’m faster now because I allowed myself to grow that muscle,” London said.

Male athletes, who face a different set of pressures, still see the consequences of that stress.

While men rarely try to lose weight in their sports, they often have the opposite problem. In wrestling, both can happen.

“In DI wrestling, a lot of them have started focusing more on lifting weights and getting bigger,” wrestling coach Tony Willaert said. “You hear horror stories of wrestlers who sit in saunas and have sauna suits on.”

In a sport with weight categories, balancing diet and exercise becomes even more difficult. It’s impossible to focus on your sport and ignore your weight in wrestling when you have a target to hit before you’re able to compete.

There are plenty of unhealthy ways to lose weight or gain it, whether it’s overeating or rapidly trying to lose water weight before a weigh-in. Either result in reinforcing unhealthy practices in athletics.

“I think the mentality of wrestlers has changed, and that’s probably the worst part of the sport. But you can’t be having ‘41 pounders wrestling ‘97 pounders, that’s just not realistic either,” Willaert said.

In order to keep athletes balanced and healthy, Willaert works with each one individually to design a weight loss or gain plan. To make that possible, the team has started consulting with Quad City Nutrition Specialists.

Wrestlers don’t need to lose or gain extreme amounts of weight. They’re encouraged to know what works best for them, whether that’s adjusting a small amount into the nearest class, or knowing they have the time to work up to a higher weight class.

When athletes are supported and have resources to manage their diet and exercise in a sustainable way, the results are more positive.

Alex Cruz, sophomore, has been wrestling for long enough to know what works for him. “It’s seeing what’s good for you because maybe what’s good for me isn’t good for everybody else on the team. It’s good to see that relationship with food and how it develops to see what works best for other people,” Cruz said.

Athletes benefit from strong relationships with coaching staff to encourage a healthy relationship to their sport. Support is essential in combating stressors from athletics.

Without a personalized plan and individual attention, athletes can struggle alone with their health, leading to body-image issues, disordered eating and unhealthy methods of staying “in shape.”

If an athlete continues to push themselves and improve, coaching staff won’t know it’s unhealthy unless an athlete were to tell them. As a consequence, over-exercising gets rewarded by coaches who would rather students improve on paper than seemingly get worse.

“My coach remarked on this one girl who got slower this season, ‘It looks like she’s gained a couple pounds,’ and that’s just triggering. I heard that and it doesn’t make me feel good. What if that was me?”Johnston said.

The common perception of disordered eating from pop culture doesn’t correlate with a motivated college athlete, and coaches are rarely trained to help students in that capacity. Students struggling with something more than meeting physical goals rarely go to their coaches for help.

“The coaches will listen to you if you go up to them and say, ‘I’m not doing great in my personal life, or ‘I’m struggling with my relationship with running,’ but their answer isn’t always the best,” London said.

In cross country or track and field, coaches can be at a loss for how to help students with issues outside of the sport. Improvement is endurance-based, and coaches want to see consistent practice from their teams.

“They’ll listen to you, but as you’re waiting for that support, waiting for that advice, it’s like, ‘Just go run, just get over it.’ It feels like they don’t care about the problem. The problem is that you’re not running,” London said.

Student athletes need support systems tailored to their wellbeing, not just their athletic improvement. A dehydrated, malnourished wrestler can’t effectively compete even if they hit their weight goal, and a runner who’s dead on their feet won’t make a good time if they haven’t let themselves fuel up.

The unhealthy practices and disorders common in athletics aren’t completely avoidable, but studies show that support systems working to demystify the misconceptions around bodies and athletic performance can help.

Further, athletes benefit from coaching staff who understand what they’re going through on a personal level.

“Everybody on the coaching staff has wrestled and cut weight at one point, so we have a lot of guidance in that respect,” Willaert said.

Empathy is hugely effective in helping student athletes through stress when it comes to shared experiences in a sport. However, shared experiences aren’t applicable to every athlete’s situation.

“All the coaches for cross country and track are all men. There’s not a single woman coach so there’s no one to relate to,” Johnston said. When students reach out for help with their mental health in addition to athletics, coaching staff is rarely equipped to help them.

“If we’re having a bad mental health day, he’s not really trained in that. He can recommend us to go to one of the counselors, but they might not necessarily know how sports affect mental health. It would be good to have someone who’s specialized for sports and how that affects athletes mentally,” Johnston said.

The relationship between sports and stress is hard to navigate. It’s harder in a pandemic, and it’s complicated by the way athletics can harm or help athletes depending on their situation.

There’s no singular solution, but there’s general consensus: student athletes need support and resources from a coaching staff who will put their wellbeing over their competitive potential.

Molly Sweeney • April 27, 2024

Taylor Roth • April 27, 2024

Chloe Baxter • April 27, 2024

Gavin Nicoson • April 27, 2024

Running on empty

April 16, 2021

Leave a Comment

More to Discover