This story is from the Observer’s Injustice and inequalities inside Augie magazine publication. Print March 2021.

When she was 11 years old, Ashanti Mobley went with her siblings to the corner store to buy snacks. But while she was waiting in line to pay, her eight-year-old brother started getting screamed at by the workers.

They yelled at him to take his hands out of his pockets and to come forward, accusing him of stealing. They told him that he had to pay for whatever he was hiding in his pockets.

The situation escalated as the workers continued to get angry, even as her brother said that he didn’t have anything in his pockets. The kids, 11 and eight-years-old, were terrified and had no idea why someone was yelling at them.

Fortunately, Ashanti’s older sister was there to defend their brother. She de-escalated the conflict, and the workers reluctantly let them go once they saw that nothing was stolen.

Although she was just 11 and didn’t fully understand what happened, Ashanti, now an Augustana senior, said it bothered her. “It didn’t make sense to me,” she said, “and it was just unnecessary.”

Later, Ashanti realized the reason for the incident was that the workers saw her brother as a young, Black boy and stereotyped him as a criminal. Ashanti said this experience forced her to develop an awareness of racism early in her life.

“Just being young and not even understanding all the things with race, I just knew that if we’re Black we’re viewed as bad,” Ashanti said.

These kinds of experiences continued throughout her childhood, starting as early as elementary school.

Anytime she asked a question in class, her teachers became angry. They’d immediately get irritated and yell at her not to act up. Or, they would remind her to behave herself as she sat quietly waiting for class to start.

As a good student and a quiet, timid young girl, Ashanti said she felt singled out and, “guilty, even though I did nothing wrong.”

“At the time, it made me want to go above and beyond with my accomplishments to prove that I’m a good, smart kid and that I follow the rules,” Ashanti said. “And then other times it would make me just kinda shut down and not want to participate or talk to anyone in fear of being accused of something or stigmatized.”

While school was a toxic environment, it also gave Ashanti an outlet for expressing herself.

In seventh grade, Ashanti’s English teacher taught her class different types of poetry. Ashanti started writing poems for class but continued to write in her free time. Specifically, spoken word poems.

“Spoken word is a very distinct cultural construct and use of language,” said Monica Smith, Augustana’s vice president for diversity, equity and inclusion. “The genius behind it, the talent behind it, is being able to rhyme when you need to but not soften or veil the message in any way because you can’t find the right words.”

The same year, Ashanti published her first free-verse poem, for which she won an award. From there, her passion for poetry grew.

“It’s just being able to carry this weight that she’s had on her, and the experiences she’s had all throughout her life, and being able to get in front of an audience, and be able to express that,” said Ashley Allen, interim director of the office of student inclusion and diversity. “And even though it is something that is hard to carry, she was willing to offer that experience to everyone else to open up and see how she’s feeling and how she’s navigating this world as a Black woman.”

Ashanti said she feels people can relate to her through her poems. She said writing poetry helps her express herself more so than just saying something.

“She’s a quiet person,” Smith said. “You’d think she was shy, she doesn’t say much. But when she does speak, you better listen.”

Ashanti came to Augie after graduating high school. As a first-generation college student, she said she was both excited and nervous to come to school. Most of all, she had no idea what to expect.

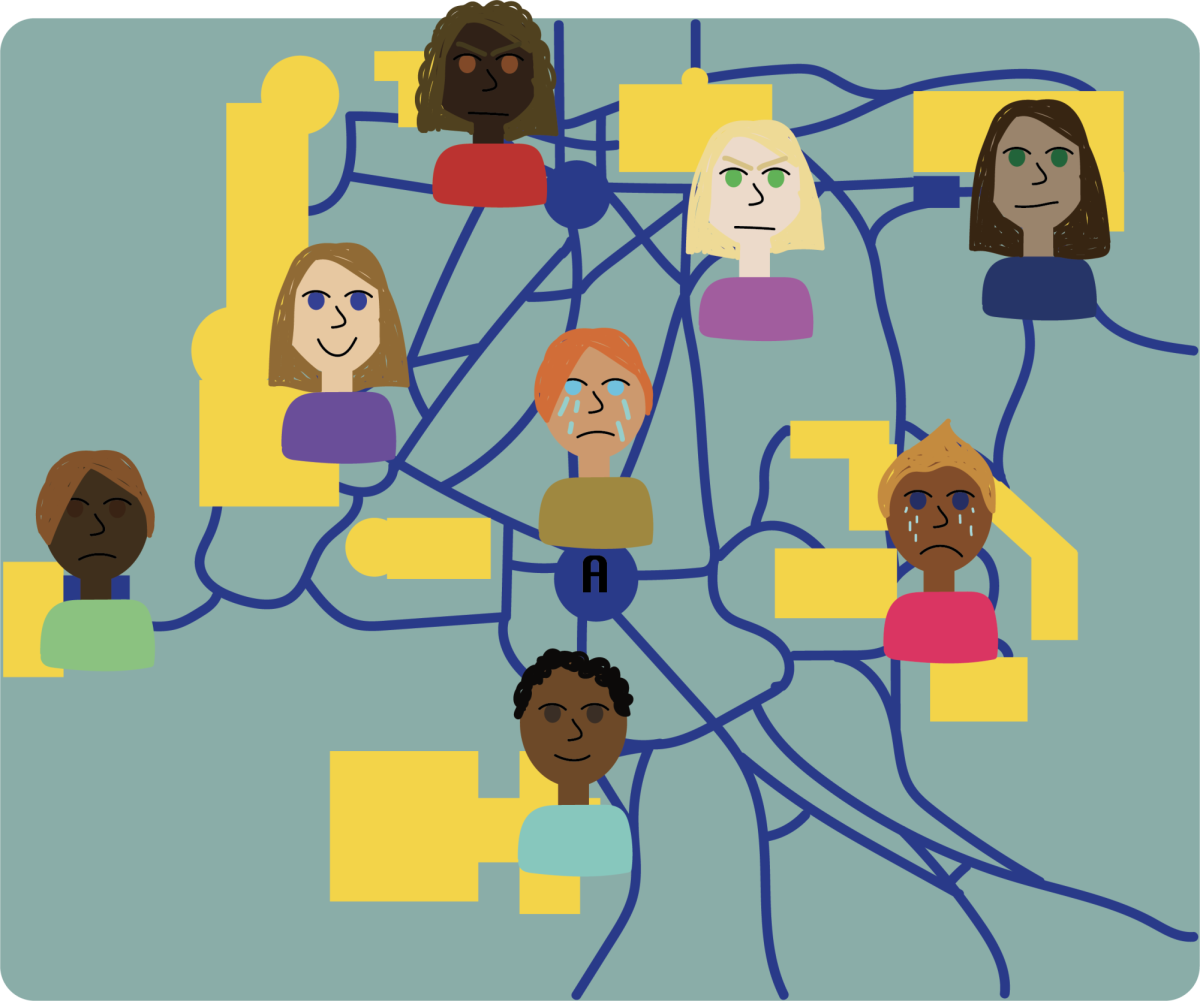

But that excitement quickly turned to dread when she got to campus her first year. Almost immediately, Ashanti came into contact with racial slurs.

She heard girls in a dorm near her singing along to the song and saying the n-word. After it happened multiple times and Ashanti got up the nerve to ask them to stop, the girls denied it and said it didn’t happen.

“Growing up [around Milwaukee], that wasn’t a word that everyone would say, so hearing it in college really kind of shocked me,” Ashanti said.

Ashanti said the fact that the girls denied saying it upset her. It took a lot of nerve to get up the confidence to express how she was feeling. When she did, all she got was eyerolls and sighs.

“It made me doubt myself and question if I was really valid in what I was thinking and feeling, and it felt like no one really cared much at first,” she said. “Like is it even worth it telling these people what’s right and wrong? Because they’re not even listening.”

The next year, her sophomore year, there was an incident where a sign was found on the Black Culture House. It had the Planned Parenthood logo and a slogan on it that said Planned Parenthood had killed more Black children than the KKK.

Outraged by the racism and ignorance of the act, Ashanti and her friend, Talayah Lemon, were part of a group that took it to administration and Student Government Association (SGA) and were frustrated with a lack of action.

So, in the spring of their sophomore year, Ashanti and Talayah organized a demonstration in the quad. They organized a gathering and speakers meant to start a conversation about inclusion on campus.

“We wanted to help protect Black students here. When you mention the KKK, that’s sparking fear,” Ashanti said. “A lot of people were uncomfortable just going into [the] Black Culture House because it was posted there. And that’s supposed to be a place where people can go and feel safe, and we didn’t feel safe.”

Since she arrived on campus, Ashanti has been committed to being an activist for racial justice. Throughout her four years, she’s organized multiple protests, given speeches and presentations and been active in groups like Black Student Union that push for racial justice on campus.

But a lot of the activism that she does is through her spoken-word poetry. As president of Dat Poetry Lounge, Ashanti uses her poetry as an outlet to express her frustrations about racism, but also about celebrating Black identity to inspire people.

“She usually writes about identity and Blackness and what that means to her,” Talayah said. “She writes things that are centered around power and they inspire and empower people.”

But Ashanti’s words, while meaningful to her, hold even more meaning with those who hear them.

“It makes me feel proud and powerful that I’m able to turn whatever I’m feeling into something for others to uplift them or give them something to relate to,” Ashanti said. “It’s like I’m doing a service for other people and to myself to share that so other people can relate and know that they’re not alone, and so I know that what I’m feeling is okay.”

Said Talayah: “When I hear her read her pieces, I can just see that passion that she has inside her. She just brings it out when she does perform, and that’s inspiring.”

The Roses

By: Ashanti Mobley

Since they snatched the seeds from their rich soil

And buried them underneath the cold concrete

Across oceans and seas, I guess

We’ve been grounded in more ways than one

Constantly trampled and stifled

I’m learning how roses can grow between the cracks of sidewalks

Maneuvering through the stomps of ignorance, racism, hatred

To reach past the skyscraper’s cast blocking the sunshine.

Systematically oppressive shadows we peer past

And stretch to catch a ray, a glimpse at least so

We rise

Like the roses in Selma, Chicago, LA, Birmingham

We rise

After the ignorance

After the beatings

And the killings

They act like they don’t know why roses have thorns

We rise

We learn

Spoke up

Stood up

You think we’d cower down?

No we keep rising

I was dreamin’

Of a people so free

Who could rise in glory

Breaking generational trauma

I was dreamin’

That raisin’ my hands in submission

Wouldn’t be taken as a submission for violence

Or an invitation for death

I was dreamin’

Of innocent black bodies with abused spirits,

Because their lives were never yours to take

I was dreamin’,

I put my fist up to show you

I won’t submit any more,

What freedom we fought for, secure in my hand

I woke up with my fist balled,

That’s my form of protection.

I mean, yeah, I can dream

But, Black people so powerful

We been makin’ dreams happen since we started budding.

The wildest dreams of our ancestors

We keep rising, makin happen what seems impossible

Fighting to make our dreams come true

Cause, that’s what roses stuck in concrete do.

Photo Above: Ashanti Mobley in a self-submitted photo.

Owen Doak • Mar 17, 2021 at 7:29 pm

Powerful poem and story. Wonderful.