Live music is back (and safer than ever)

White Tornado interacts with the crowd during his exciting performance at Chill on the Hill on Sunday, Sept. 26.

October 10, 2021

Sunday afternoon, Sep. 26, found me sitting on a blanket at the Lefty Anderson pavilion waiting for a friend to join me for an outdoor concert. Augustana had tried to hold Chill on the Hill back in 2019, but it rained. Certain global events led to it being put off in 2020. So, in 2021, I was excited for a few hours of local music with good company.

Live music has been out of reach for most Americans until recently. Aside from the bands at Kavanaugh’s playing loud enough to shake the walls of my dorm last year, I didn’t see any local musicians before I spotted a couple of buskers at the Freighthouse farmer’s market last spring.

Summer brought tour announcements, and with them, sizable hits to my credit card balance. One week in June, I charged tickets for three different concerts to my account.

In my defense, I was excited. I started working at a record store at the beginning of the summer and fell headfirst into the music scene in a way I never had before.

But while June provided hope for a fall packed with pandemic-free events, late summer was full of emails updating me on the status of my tickets. One show was moved to an outdoor venue and changed dates. Another asked that I purchase ticket protection in case the show was postponed. One by one, they each required proof of vaccination, photo ID and masking, which was not a problem for me.

It felt like any day I would get the email that the shows were canceled as cases grew. I began to see more and more customers mask consistently again and readied myself for the cancellation notices.

Not to be deterred by COVID-19 concerns – a phrase I would have shuddered at this time last year – I requested off work for the date of the first show. It was the night of Aug. 23. I was assigned to move in the morning of Aug. 24.

Here’s the thing about being 20, enthusiastic and previously used to running on empty: you can convince yourself it’s easy to drive to Milwaukee for a show, leave the city just before midnight, and sleep a few hours before waking up to move across state lines in time to attend a midday job training. You do stupid things.

As stupid as I may be, sometimes it works.

People are desperate for anything resembling life before COVID-19. That’s the draw to live music these days. It’s a communal activity where you experience something (in-person!) with the strangers next to you. Music is reactive. It’s the best.

More than going to the movie theaters or other back-to-normal activities, concert-going relies on an exchange between the musician and the audience. It’s the antithesis of a lagging, awkward google meets session.

We’ve all missed something like that. So when I stood in the first few rows of the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee with an old friend, a paper band fastened around my wrist, a year and a half of anticipation burned in my veins.

Of course, the night wasn’t without reminders of the mid-pandemic world. We showed our vaccination cards and IDs at the door (for individuals unable to receive the vaccine, a negative test within two days of the show has also become a standard practice) and found good seats close to the stage. A few minutes before the opener came on, we watched as the man in front of us received a text that he had been exposed to a positive case earlier that day.

We saw him respond with frustration, saying he would go get tested the next day. He said he didn’t know what to do. He told his coworkers they could take the rest of the weekend off. He didn’t move.

The man texted his friends about the exposure before lifting his phone to take a picture of how close he was to the stage.For every minute I spent a few feet away from him, the worse I felt.

Knowing that I would only feel worse as the night went on, I tapped him on the shoulder, saying, “I know this is a huge invasion of privacy, but…” and let him know that I had seen him receive a message about a positive case. The man was conciliatory. He apologized and went towards the back of the venue after giving me the rundown on the situation. I didn’t see him for the rest of the night.

The whole time, I couldn’t stop thinking about being in a room full of vaccinated people. The certainty that we were all on the same page about health and safety was a new feeling after a summer full of watching people roam maskless around town.

Thanks to mandatory masking and required vaccination, artists and venues can immediately prevent problems arising from varying stances on COVID-19 prevention.

Masking and vaccination requirements reduce conflict and guarantee a shared goal to stay safe among audience members. When everyone in the audience poured onto the street after that first concert, many of them hesitated to remove their masks until long after they had left the building. The ones who lingered outside the venue spread out on the sidewalk, an instinct from social distancing.

It was a smaller show for a band that drew an older crowd, so I wasn’t too worried about rowdy college kids disregarding COVID-19 regulations. Attending a much larger show on Sept. 12 was an entirely different experience.

The line going into the show packed itself towards the entrance, with many of the people masking only once they got inside the venue. Plenty of folks removed their masks when they had found their own space on the grass.

Since it was outdoors, plenty of the concertgoers were cavalier about pandemic protections. In the pit, a girl standing in front of us constantly let her mask slip below her nose while she yelled into her phone. Later, she and her friends completely removed their masks to take photos during the set.

As the crowd dispersed, people discarded their masks. Outside of lines and crowds, most concertgoers treated the masking requirement as optional. As I chatted with the venue’s security guard, we watched a group of seven or eight people leave their masks in a pile on the ground to take a group photo.

To its credit, much of the crowd was respectful. For one thing, no one around me was notified that they had been exposed to COVID-19.

It’s impossible to ignore how an audience will be skewed by the artists’ listenership. At a Phoebe Bridgers concert, the crowd is more likely to follow regulations than at a show for an artist who has spoken against government restrictions.

(Mid-show, Bridgers changed a song lyric from “…we hate Tears in Heaven” to “…we hate Eric Clapton” after Clapton released a song criticizing mask mandates and other protective measures.)

At Laborspace, the Labor Day weekend concert presented by Ragged Records and Rozz Tox, the Rock Island community gathered for an afternoon of poetry readings and performances from a few local music acts.

A number of Augustana faculty attended (as some were performing), and I counted myself among the few students in the crowd. We laid out a picnic blanket in the greenspace between the two businesses and masked when social distancing wasn’t possible. Rock Island residents in attendance chose to mask or not based on personal preference.

While restrictions were looser than in an established music venue, people milled around freely and if someone asked them to keep their distance, they would. For a few hours, my friends and I enjoyed the afternoon without anyone getting in our space.

What the Laborspace event lacked in vaccine checks and mask mandates, it made up for in communal accountability. People understood they were there to support local creators and did so respectfully.

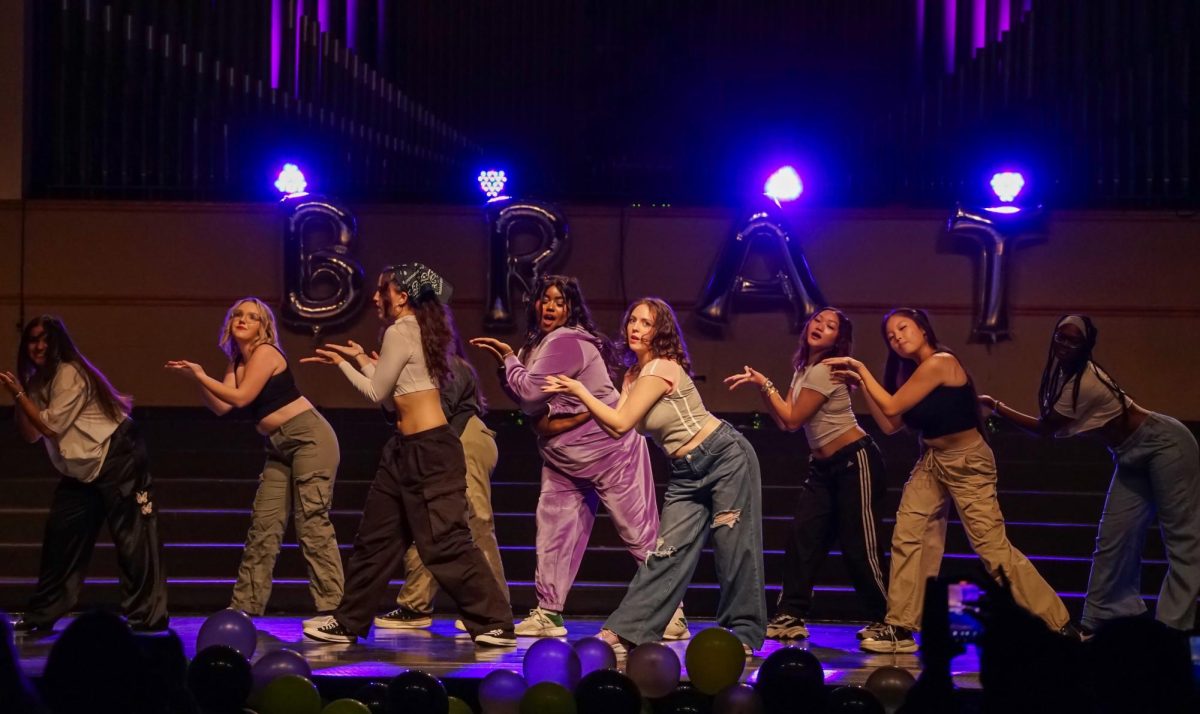

Luckily, Chill on the Hill turned out to be much the same. While only a few people were masking, groups were easily more than six feet apart. Small clusters of students, faculty and locals set up their blankets and chairs across the whole space of the pavilion, opting to stretch out and get comfortable in the nice weather.

These shows don’t depend on the clear, easy measures of safety bigger concerts have. When it comes down to it, local events are about coming together. Everyone wants to have a nice time, which means considering the comfort of the people around you.

It’s been too long since we were in the practice of taking care of the people near us. These local concerts and other events provide an opportunity to show up for our community, something I have found a love for during the pandemic.

Misery loves company but so does joy. There’s a reason half of Augustana drove to Chicago to see Harry Styles perform a two year-old album on Sept. 24 and 25. Music makes us feel like we’re a part of something, and that feels really, really good these days.