Pursuing an undergraduate education demands a significant time commitment. Yet, most students still choose to get part-time jobs, adding even more responsibilities to an already overwhelming schedule. More surprisingly, some even deliberately work more than they are legally allowed to, jeopardizing both their physical and mental health as well as their education.

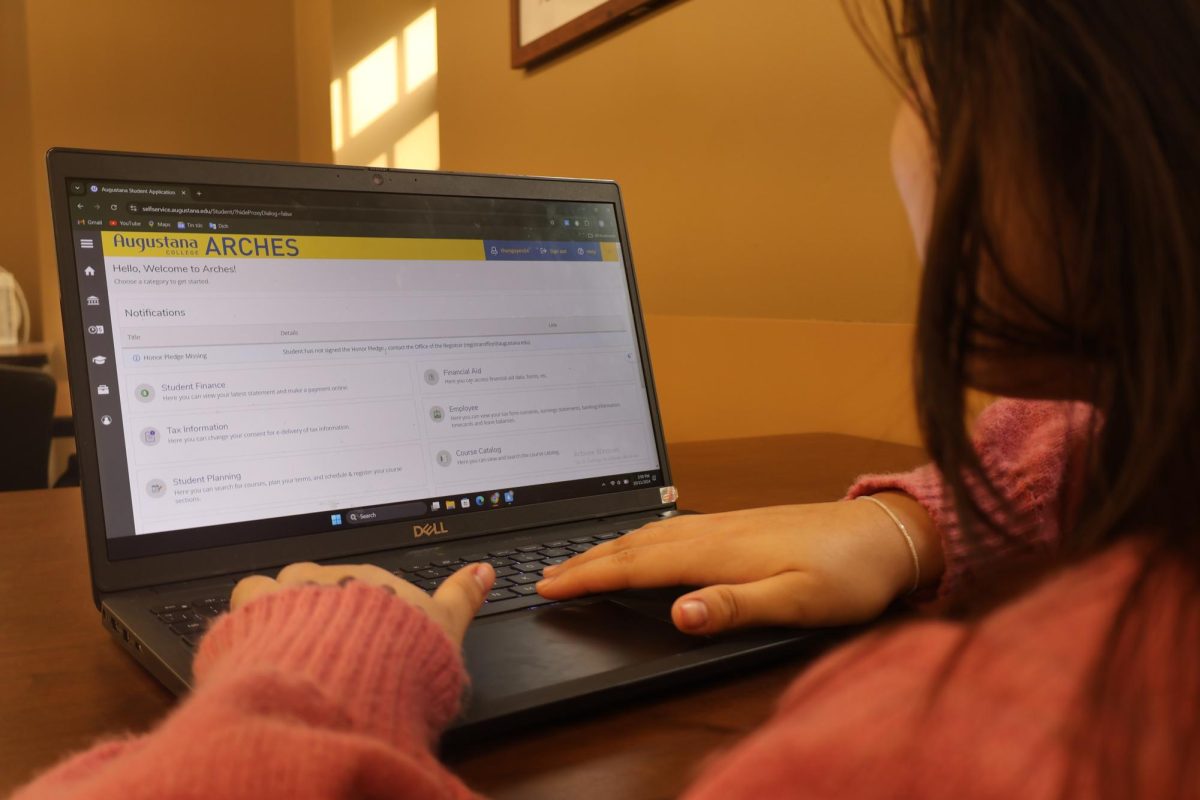

On Sept. 10, 2019, students at Augustana College received an email reminder about the working hour limit for student employees with on-campus jobs. Apart from re-emphasizing the rules and policies regarding student employment, the email also mentioned instances where students had exceeded the hour limit, clocking in more than 30 hours within a week, and the consequences for such actions.

The Observer sought to find the reasons behind this phenomenon and in the process, learned more about the work culture of Augustana students.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the average cost for attending and living on campus at four-year private nonprofit institution for the 2017-2018 academic year is $50,300. Augustana College charged its students $51,222 that year. This is only the sticker price, but even after deducting scholarships and financial aid from it, the cost for a college education is still substantial, not to mention the miscellaneous expenses that students need to pay while in school.

“My parents aren’t able to support me in that way [miscellaneous fees], so in order to continue to go to school and pay for both school and necessities, I needed a job,” Lily Tewksbury, a senior at Augustana College said. “It’s also for fun things as well. If I want to go out with my friends or be in my sorority, I need to work to afford it. On top of that, I do feel a little pressured to work because society as a whole does have this [mentality] that if you’re not working, you shouldn’t be doing anything fun because you’re not earning it.”

Juliette Camara, another senior at Augustana College, also had financial reasons for choosing to work while being a student.

“It’s mainly for money,” Camara said. “I don’t really enjoy some of the work that I have to do, especially if they have nothing to do with my major, but it’s just so expensive to be here so me working is the only way I can afford [it].”

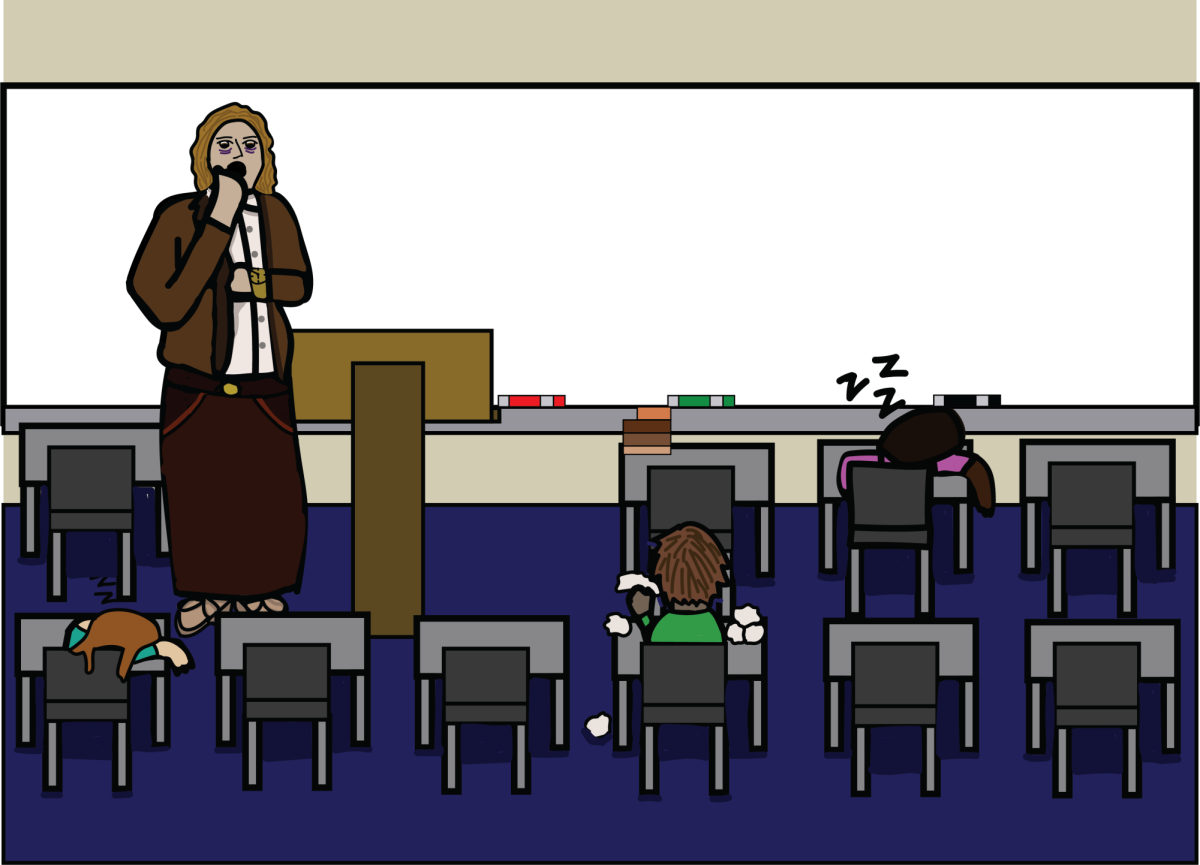

It is not at all uncommon or bad for students to get jobs solely for the money. However, the lack of interest combined with the part-time nature of these jobs can lead to students not prioritizing their work. This is especially true for on-campus jobs. Speaking from her own experience as a student supervisor in the Dining Hall at Augustana College, Camara said, “Most employers on campus understand that you’re a student and are really helpful and willing to adjust things, but you don’t want to just be like ‘Oh, I went out Saturday night. I don’t want to come to my shift Sunday morning.’ That’s not okay. You want to treat this as a real job because it is a real, paying job even if you’re only a student.”

International students, which make up 12 percent of the student body at Augustana, face unique challenges of their own. Camara, a student of French nationality, expressed, “As an international student, I only get to work 20 hours and with the pay, it’s not enough for me to cover my tuition that is already higher to begin with and is still increasing.”

Although international students can work up to 20 hours, they are not allowed to find jobs off-campus because of their F-1 and M-1 student visa forms, which restrict work to only on-campus jobs, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. After the initial year, international students may be allowed to work off campus, but only if it is related to their area of study and approved by the school. This may inhibit more desirable pay in other jobs compared to the minimum wage Augustana is paying its student workers.

International students also find more difficulties in securing internships compared to their domestic peers. Laura Kestner-Ricketts, the Executive Director of Career and Professional Development at CORE, explained, “There is a whole other set of challenges that our international students have in finding jobs and internships. . . There are many employers who do not want to hire international students because there is that risk that they may not be able to work there long term. As a result, there are some employers who don’t even want to hire an intern who’s an international student because once they are an intern, they may not be there for the long term.”

Genesis Sarmiento, junior, works as a supervisor in the dining hall. Sarmiento’s job involves numerous tasks, including, restocking supplies and picking up vacancies.

“It’s smooth sailing,” Sarmiento said. This year Sarmiento was given the title of supervisor after working in the dining hall for two years.

The reason for Sarmiento’s added responsibilities came after her desire for adding more to her resume. Sarmiento’s new position requires her to work a minimum of 15 hours a week.

“There are days that I don’t get enough sleep,” Sarmiento said. “I have to be more on top of stuff with time management.”

Sarmiento would call her time management a work in progress. Her longer hours at work is making it harder to fit in any social time.

Money isn’t the main factor for getting the dining hall job, as Sarmiento doesn’t have a meal plan.

“I fill the [to go box] to the brim,” Sarmiento said. “The dining hall and campus cupboard is where I get my food.”

This decision is logical because she doesn’t have to cook herself and can eat a meal while she is on the job.

For many students, working, either through jobs or internships, acts as a supplement to their study. “[My] internship was to gain experience and decide what I want to do with my life, to see if my major was the right one. [It] helped make my résumé more interesting and allowed me to network with people,” Camara, majoring in Multimedia Journalism and Mass Communication, said about her internship. “I almost consider my internship as a class, just a different type of class than a traditional one.”

Some even found what they want to do post-graduation through working. Such was the case with Tewksbury, a Communication Sciences and Disorders major who found her passion for helping kids through her multiple jobs.

“I started working in the school that I’m [currently] working at in sophomore year and got in contact with the speech pathologist at that school,” Tewksbury said. “We became friends, and talking to her about what she does in the school made me realize that being an SLP [speech-language pathologist] is what I want to be. Doing ABA [Autism Behavioral Analysis] over the summer really solidified that this is what I want to do.”

Sarmiento wants to participate in two different internships, computer science and accounting. After numerous career fairs, Sarmiento planned to schedule classes around an internship in the upcoming summer and during her spring term senior year.

Sarmiento hopes that these internships will help her figure out exactly what she wants to do after Augustana.

Working also presents students with some challenges despite the financial and professional benefits it brings.

“Trying to figure out how to balance work and school is definitely a mental strain,” Tewksbury said. “There are times when I will be at work and so I can’t finish my homework or the other way around where I can’t work because I have class. That wears me out both physically and mentally. There’s never a time when I get to be ‘off’. I’m ‘on’ all the time, if not for school then for work.”

Sarmiento says her mentality focused solely on the negative effects of failure. She details her passion of learning to code to make herself more competitive in computer science, yet during her struggles, Sarmiento’s mindset was negatively affected.

Sarmiento mentions that her mindset on failure has caused her to cry and feel isolated.

On Symposium day, Sarmiento attended “Failing Big, Living Well,” where she learned how failure can be a positive component in her life. Dr. Elizabeth J. Stigler, an Augie alum, held the symposium event.

“This was perfect for me,” Sarmiento said. “Failure is not a bad thing. It is an opportunity for growth. If I change my mindset it’ll be alright. Stay positive and not dwelling on the negatives. Whenever I fail, I see what the next steps can be and what to do next time.”

Additional reporting by Brady Johnson

Graphic by Kevin Donovan