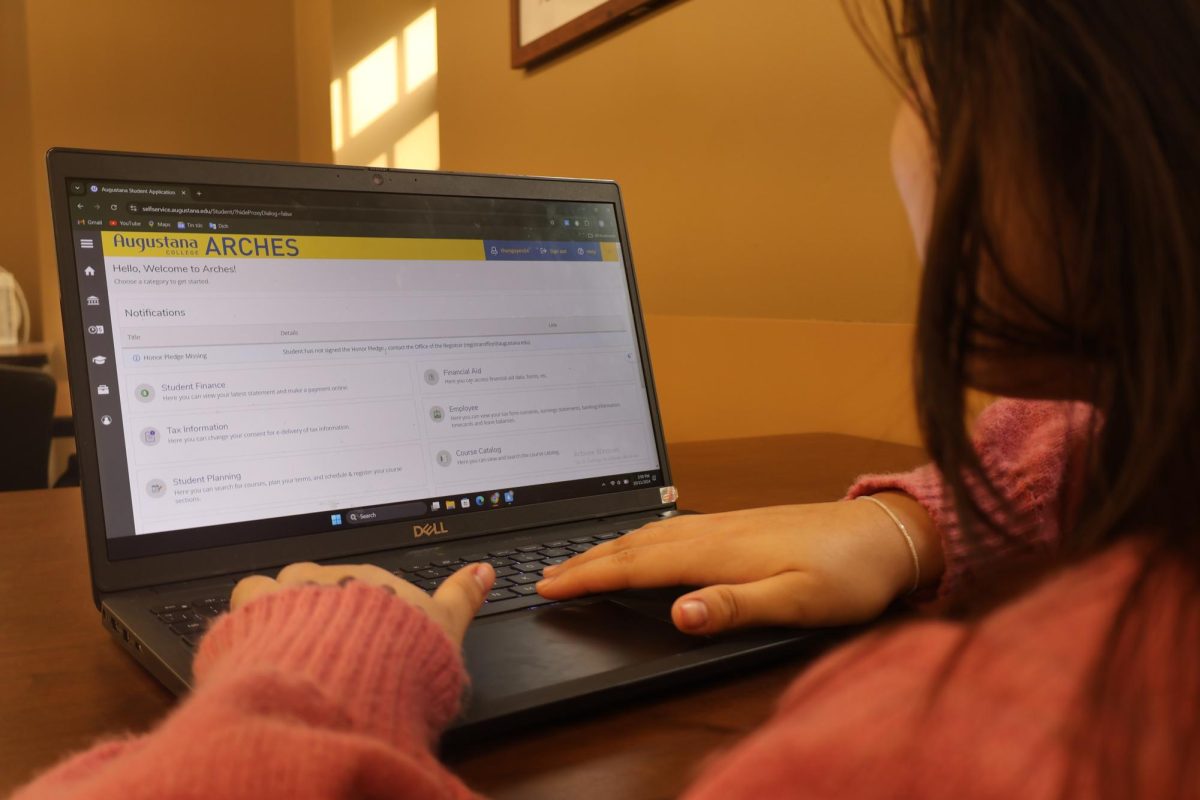

Countless emails bombard student and staff mailboxes on a daily basis. It is a constant flow of information that is either useful or meaningless. In the last six months, 24.5 million emails were sent over Augustana’s email server. Yet, no matter the priority of the email, it is forever held and can, under guidance, be monitored by the college. Digital data is not secure. Yahoo had 3 billion user’s data breached in 2014. Willful transaction of data like the actions committed by Facebook with Cambridge Analytica are just some types of unethical data exchange. One thing is clear: our lives are not as private as they once were.

Terms of agreement and countless application updates appear to hide new ways of data collection that are unbeknown to users. With the mass volume of users on major platforms, it is difficult to paint a clear picture of engagement. On a college campus composed of 2,500 students, the policies of engagement could be easier to examine, unlike Google and Facebook.

In the handbook under computer, email and Internet usage, a line reads: “email is not private or confidential. All electronic communications are college property. Augustana reserves the right to examine, monitor and regulate email messages, directories and files, as well as internet usage.”

These policies are only defined for the faculty while students are held to a different standard.

“Our students are held to a looser standard than employees are,” Chris Vaughan, chief information officer of ITS, said. Vaughan has been with the ITS department at Augustana for over 20 years. Throughout his time here, he and Scott Dean, network manager, have set the norm for monitoring.

“We don’t actively monitor emails” Dean and Vaughan repeat. Questions linger on how Augustana handles student data. How does one initiate a process of monitoring? Who can access student and staff emails?

If Dr. Wes Brooks wanted to see a staff or student email account, he would have to go through Dean and Vaughan to issue a request. Vaughan mentioned that this request could be done over email through a work order so that, in Vaughan’s own words, there is an “audit trail.” According to Vaughan and Dean, they would ask another administration member, in this situation, about Dr. Brooks’ request utilizing a double verification system.

These work orders would need to be legitimate reasons for ITS to even consider allowing any content monitoring. Dean continues using Dr. Brooks as a figure in this hypothetical scenario:

“If Wes said I want you to look into that person’s email and look for this specific thing, I am not sure I would even feel comfortable doing that,” Dean said. “I might go [he moves his laptop over] you do it. I’ll log you in and you look for it. I don’t want to see it. I think that is how I would address that. Let someone at a higher level do that rather than me do it because you don’t want to see something I don’t need to see. I would want someone else to look for it specifically.”

This norm of engagement was created by what they think would be necessary for a formal process. Dean and Vaughan both affirm that the administration has never requested access to a student or staff email account to see content since they have been in their respective positions, which again is around 20 years.

Squabbles over homework have led to requests for ITS to check whether or not a student has signed into their Google account. These occurrences were few and far between according to Dean and Vaughan.

Initially, the process involved checking “meta-data” to see if a student sent emails to a particular professor who was asking to make sure they sent in an assignment. Dean calls these “email transactions,” which means they could see the sender and receiver as well as the subject line. However, they wouldn’t see any content. Dean gave a scenario using Professor Bob Tallitsch, a retired Augustana employee, to showcase how the process would work.

“Professor Tallitsch says this student never emailed him the homework but the student says, ‘no I sent it Sunday night,’” Dean said. “They’ve gone back and forth. Professor Tallitsch might go to the dean’s office and say, ‘I really need proof that I am not losing my mind and I did or didn’t receive this.’”

He states that the dean’s office would notify him of the requested search.

“I would run a search on that and I would go, ‘yes, there were three subjects of one, two, and three’ or ‘no there was none,’” Dean said. “I would give that information back to the dean of students. Again I don’t actually see the content. I can’t see the content.” The scenario is uncommon as Dean states that most questions regarding sent homework are settled between the student and professor.

“We don’t operationally check email, view email and anything like that… monitor email, but we reserve the right to under certain circumstances,” Vaughan said. What are certain circumstances? The answer comes down to the health and safety of the student.

Dean and Vaughan spoke at lengths that any monitoring of email was avoided. In the case of a missing student, an exception is made. Vaughan mentioned that the dean of students office would request assistance after all other avenues were tried. These avenues would be talking to friends, professors and other individuals who may have been in contact with the student in question.

Again, Vaughan wants to point out that even in this case, a simple check to see if they logged in would hopefully be sufficient in finding the student.

“If a student goes missing… there are other ways I can see if they show up on the radar…before we go into their mailbox.” Dean said. “It’s a last resort. It’s like going into their room and going through their drawers. We don’t do that without any good reason.”

Dr. Wes Brooks, dean of students, agrees with Dean and Vaughan that any utilization of ITS would come after all other avenues were tried.

Student records, including grades and other academic information, are protected under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). This means any parents or outside individuals would be unable to access student information.

Calls coming from parents and grandparents to the dean of students office are turned away because most students at Augustana are over 18.

“If students are interested in having their information shared,” Dr. Brooks said. “Specific buckets (specific information) shared with parents and people outside Augustana I would encourage them to visit the Registar and fill out the FERPA agreement.”

Students with no exceptions listed appear to want their data secure from any and all outsiders.

Vague data including the number of majors and most basic information found in the student directory could be given to outside studies that the college deems appropriate. This information is not personal to the student, so no FERPA violations occur. Even then, Dr. Brooks state, the college scrutinizes any research proposal involving overall data from the institution.

When it comes to student privacy, the main factor in guiding the policy is FERPA. For Augustana, it is robust enough to cover their students, according to Dr. Brooks.

When it comes to in-house policy, however, there is not a formal document. Everything said by Dean and Vaughan were personal practices and not written into policy. Vaughan said that is because there has never been an issue with student and staff privacy. As Vaughan and Dean guard the gate there appears to be no worry for intrusions.

A policy would outlast personal practices.

“That is a good point with the turnover absolutely,” Vaughan said. “We are collaborating to redefine to make sure the same texts of the definition on the student website and employee website match. I think you found an area that we probably need to focus on here, but you know again, candidly, I don’t know when that will be in the next six months to lay down policy and publicize it.”

In the meantime, student data is safe from intrusion, unless the student, like many consumers, flood the web with their information. Once something is sent, it is online forever.

Illustration by Brady Johnson.

Categories:

Emails, data and privacy in the tech era

March 19, 2019

0

More to Discover