Decades after its founding at Augustana in the spring of 1968, alumni are coming home for the 50th anniversary of Black Student Union (BSU) on homecoming weekend, Oct. 5 and 6.

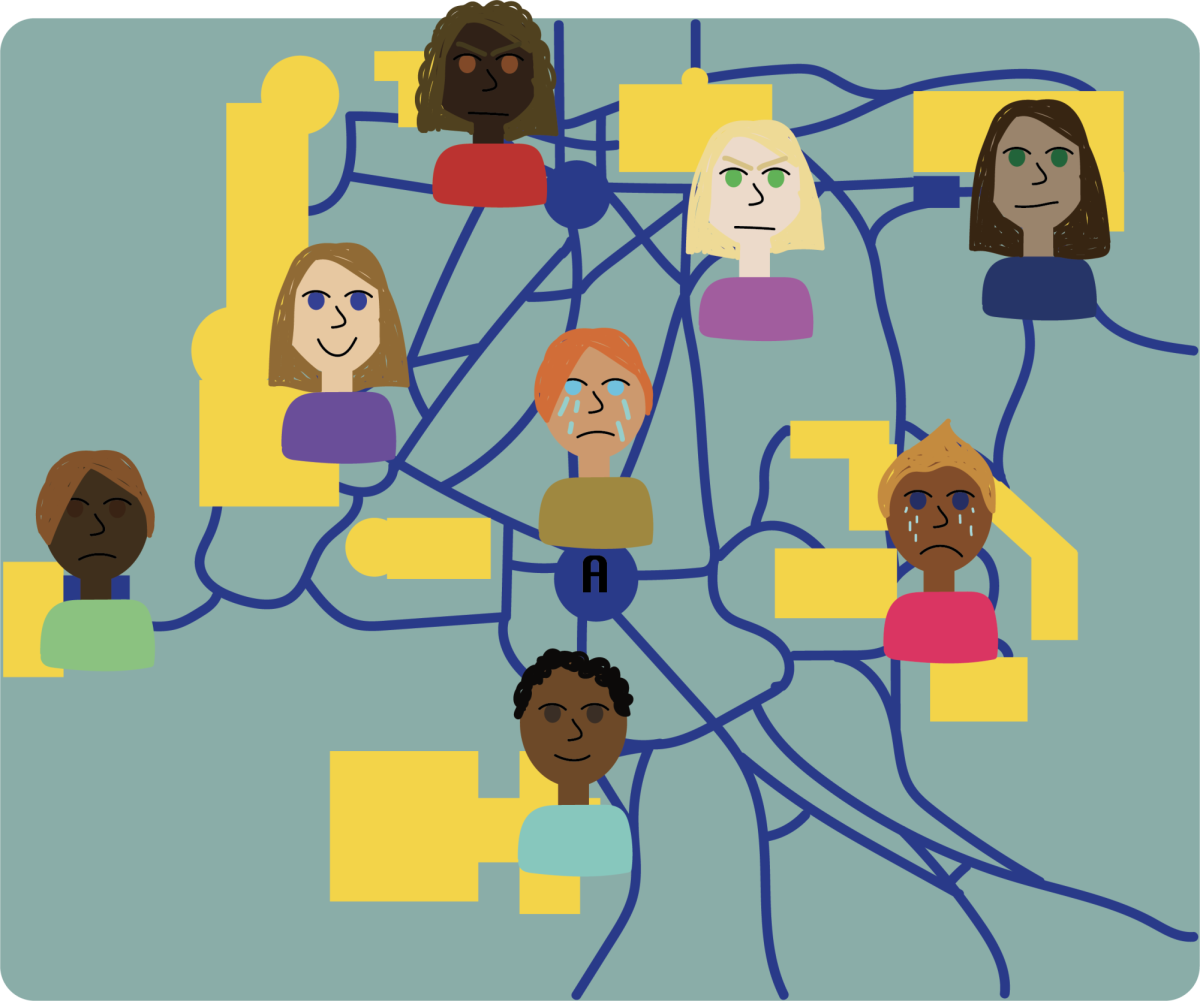

At a time of national unrest and mounting racial tensions during the Civil Rights demonstrations in the ’60s, Augustana’s BSU was founded to provide support for black students at a predominantly white institution (PWI). It has endured for the past 50 years and caused an evolution of growth not only within its own group but in culture and diversity groups throughout campus.

When Thomas Collins, jr. and Wilbon Kelley (’72) went to Augustana, there were 12 black students in their class and 5 black students already on campus. With that lack of representation, Collins and Kelley said there was no place for them to go on campus before BSU.

“There was really no place for us to go to socialize with other African-Americans. We just needed a place where we could be ourselves,” Collins said. “The purpose we served was to have a voice on campus, because at that time, being a very small minority, we felt like we were invisible. That’s why we went through the channels to protest and perform civil disobedience – to have a place of inclusiveness where we could socialize, study, party and share our common backgrounds and ideas and thoughts.”

According to Michael Rogers, director of the Office of Student Inclusion and Diversity, 50 years of BSU is a milestone that needs to be celebrated and honored.

“The Black Student Union paved the way for a lot of other culture groups that exist today and have changed the campus climate to make it more welcoming – they had a huge part in that starting in the 1960s,” Rogers said.

For current BSU president, sophomore Jordan Cray, the group’s rich history is moving. With a new administrator (Dr. Monica Smith) and office dedicated to inclusion, Cray said she couldn’t help but feel thankful for the initial struggle of BSU’s founders in 1968.

“BSU was the beginning point. It was the first culture group on campus, so I think it provided inspiration for other groups,” Cray said. “Besides bringing social awareness and trying to get civil rights together, the group started so people could have a voice and be themselves without the fear of being judged or attacked.”

According to Cray, the need for a Black Student Union is just as real as it was 50 years ago, which is why the group has endured.

“BSU is needed on campus. For me, coming to Augustana is a bit of a culture shock because it’s my first time being at a PWI,” Cray said. “I needed a different type of space, and that’s what keeps it going – other black students need that space, too.”

Regardless of the years between them, alumni and current students alike agree that the goal of BSU has always been to create a safe space for black students on campus.

“The best way we could put it is that was our refuge,” Kelley said. “That was where we could be unguarded and 100 percent comfortable to be ourselves. We came in as freshmen in 1968 when there was no Black Student Union and there was a very low minority presence on campus.”

Now, however, the objective has shifted. According to Ashanti Mobley, vice-president of BSU, the mission is now to encourage the inclusion of students from all different backgrounds and cultures to take part in learning about black struggle.

“Black students know mostly about black history and struggles toward black people, so it’s mostly other races that we’re trying to get to come and see us because they don’t know about these things,” Mobley said. “It’s important on this campus to get an understanding of people who are different than you because that helps us connect.”

According to Collins, the college has made steps toward increasing multicultural diversity on campus. However, he still sees a need to increase recruitment of African-American students.

“Something I notice between the BSU from 50 years ago to the BSU today is that it was strictly African-American. Now, I see international students and African students and other culture students,” Collins said. “It has become more multicultural; campus has become more culturally and ethnically diverse, but I would like to see the school step up its game recruiting African-American students.”

Historically, Black Student Union has also played a role in inviting famous black activists, politicians, athletes and comedians to give speeches at the college. Some of those guests were even featured at the 1969 Black Power Symposium Day, only one year after BSU was founded: Jesse Jackson, the Black Panthers, C.S. Smith, Dick Gregory and many more.

“The founding of the Black Student Union was a great catalyst for ethnic and minority change on campus. We kept on seeing the classes of minorities increase after founding the BSU. Augustana started an African American studies program, and in 1969, we had Black Power Symposium Day,” Collins said. “It was probably the largest symposium of African-American leaders in a college at that time. We got the administration to take note of the importance of ethnic diversity, and they even sponsored two of our classmates to go to Africa for a term. We felt they were really listening to us, and that changed everything.”

As an organization, its accomplishments have been so significant that other groups have come out of BSU to provide more specific support systems for students of color. One of those groups is the Ladies of Vital Essence or L.O.V.E., a non-Greek sisterhood based on service, which was founded in 1980 to empower women of all different races and backgrounds.

Though the group was originally founded by women of color, vice president and junior Ruth Nwathu said L.O.V.E’s mission is to be a group of positivity that embraces all kinds of women, not just women of color. Nwathu, like many other students, didn’t know about L.O.V.E’s existence until she asked her advisor for volunteer opportunities on campus.

Now, she couldn’t imagine her college experience without L.O.V.E.

“It’s important to have an organization at Augustana that represents women of color. Sometimes when I walk into a classroom, I might be the only black person . Having a group where I see people who look like me who might not necessarily have been through the same experience but who kind of understand where I’m coming from as a woman of color and the challenges we do have to face on a daily basis is really important to me,” Nwathu said. “Like my hair! Some people might not understand, but for me, that’s a big deal – having a place where I can talk about issues and where we can empower each other and make each other feel like we’re not alone… it’s a real sisterhood.”

Different than the social Greek groups at Augustana, L.O.V.E’s focus is on service and community, organizing projects that seek to benefit survivors of domestic violence, local non-profits and even schools like Longfellow Elementary.

However, Nwathu added, because the group isn’t as focused on social activities as heavily as service like other Greek groups are, the challenge has been in recruiting members who are committed to giving back and supporting each other. L.O.V.E currently has 7 members.

Nevertheless, Nwathu has found herself better because of the group.

“I didn’t consider myself a leader, but being in LOVE gave me a voice where I felt like, okay, I can do this,” Nwathu said. “I am able to actually organize something and lead a service project and be good at it. We’re all about that – women empowerment.”

Other groups that have come out of BSU are the Magnificent Gents (no longer active), the Multicultural Men’s Association (or MMA, founded by Michael Rogers in 2015) and arguably, all the other culture groups at Augustana.

In the past and today, some of the same responsibilities have been shared by members of BSU: to create unity and encourage activism on campus.

“We protested. I’m proud to say that black students protested,” Collins said. “We demanded a black house and ethnic diversity during homecoming. We had a sit-in at the president’s office. We demanded acknowledgment, and that’s when administration stepped in.”

According to Mobley, one of the biggest challenges the organization faces is creating unity for black students at Augustana and erasing the stigma that BSU is only for “people who are too radical, who sit around and whine and do nothing.” Mobley has seen a disconnect between black students who go to BSU and black students who are involved in other organizations on campus, who may not want to associate themselves with the negative stigma.

“What we want to do is squash any beef we may have and just get together, because when it comes down to it, we’re all black students. Even if people might not want to identify as that, it’s still a connection that we have,” Mobley said. “Having that unity is something that can help us feel like we have a space on campus. We’re trying to show BSU is open to everyone no matter what their background, which is a challenge.”

When Rogers attended Augustana, the need for activism was less imperative than in 2018.

“The challenges BSU is facing now – for the most part – did not exist when I was a student. The history and foundation of BSU is activism. We really didn’t have some of the issues now that students are faced with, even though it was only 10 years ago,” Rogers said.

In the past few years, BSU and other culture groups like Latinx Unidos have become more active members pushing for social change, demonstrating in protest of the 2016 chalkings, kneeling like Kaepernick at the homecoming football games and advocating for an office of inclusion and diversity.

“I think what students are experiencing now is just a reflection of the current time we live in. When I was a student, President Obama was just elected. We had our first black president, and I think that really informed a lot of campus culture,” Rogers said.

For Cray, the increasing activism is just indicative of what Augustana has taught her.

“That’s the greatest lesson I’ve learned at Augustana,” Cray siad. “If you want to see something done or changed, take the initiative and start it.”

When Rogers was a student, there were about 15-20 members of BSU. Now, there were 200 students who showed up to the first meeting, a sign of hope for the growth of the group.

“Without BSU or the passion for it, I wouldn’t be at this school. I feel like going into that space is like home. I grew up around black people, and having that space where people can know where you’re coming from because you may have been subjected to the same things is helpful. Not all of us have the same background or grew up in inner-city areas and it’s not the same for everyone, but we can relate to each other,” Mobley said. “I want to help make it so people can create BSU as their own so they feel like they have a space. I don’t want people feeling like they don’t have a place to go, whether they’re black or not.”

If he’s around for the 100th anniversary of BSU, Rogers said, he’d like for the legacy of the group to be positive.

“I would like to leave a legacy of students really feeling empowered in that the BSU was a safe space for them to explore their identities and develop and grow while they’re at Augustana,” Rogers said. “I would hope that in 50 years, we’d have a lot more to celebrate as far as what the group has accomplished.”

For more information, BSU’s extensive history can be viewed through the manuscripts and photos at the Augustana Special Collections on the first floor of Tredway Library, open from 1-5 p.m. on Monday to Thursday.

Photo featured above: Civil Rights activist Dick Gregory speaks at the Black Power Symposium Day in 1969.

50 years of Black Student Union

Thea Gonzales

October 4, 2018

0

Tags:

More to Discover