Teen homelessness is a problem in the Quad Cities that local governments are hoping to stamp out with money and cooperation with local agencies. However, most city administrators seem more concerned with keeping Quad City residents in their homes.

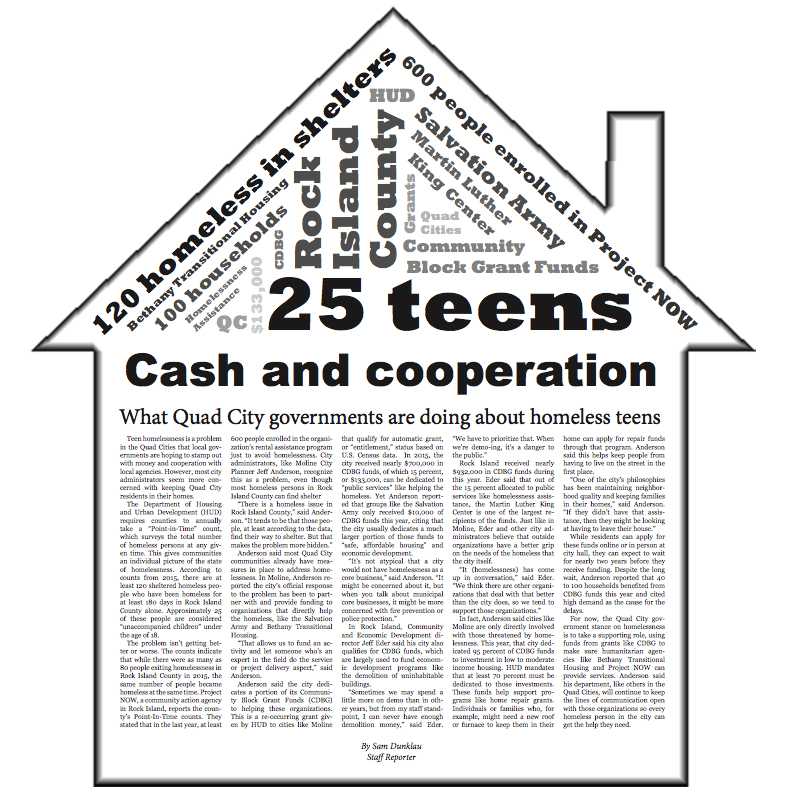

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) requires counties to annually take a “Point-in-Time” count, which surveys the total number of homeless persons at any given time. This gives communities an individual picture of the state of homelessness. According to counts from 2015, there are at least 120 sheltered homeless people who have been homeless for at least 180 days in Rock Island County alone. Approximately 25 of these people are considered “unaccompanied children” under the age of 18.

The problem isn’t getting better or worse. The counts indicate that while there were as many as 80 people exiting homelessness in Rock Island County in 2015, the same number of people became homeless at the same time. Project NOW, a community action agency in Rock Island, reports the county’s Point-In-Time counts. They stated that in the last year, at least 600 people enrolled in the organization’s rental assistance program just to avoid homelessness. City administrators, like Moline City Planner Jeff Anderson, recognize this as a problem, even though most homeless persons in Rock Island County can find shelter

“There is a homeless issue in Rock Island County,” said Anderson. “It tends to be that those people, at least according to the data, find their way to shelter. But that makes the problem more hidden.”

Anderson said most Quad City communities already have measures in place to address homelessness. In Moline, Anderson reported the city’s official response to the problem has been to partner with and provide funding to organizations that directly help the homeless, like the Salvation Army and Bethany Transitional Housing.

“That allows us to fund an activity and let someone who’s an expert in the field do the service or project delivery aspect,” said Anderson.

Anderson said the city dedicates a portion of its Community Block Grant Funds (CDBG) to helping these organizations. This is a re-occurring grant given by HUD to cities like Moline that qualify for automatic grant, or “entitlement,” status based on U.S. Census data. In 2015, the city received nearly $700,000 in CDBG funds, of which 15 percent, or $133,000, can be dedicated to “public services” like helping the homeless. Yet Anderson reported that groups like the Salvation Army only received $10,000 of CDBG funds this year, citing that the city usually dedicates a much larger portion of those funds to “safe, affordable housing” and economic development.

“It’s not atypical that a city would not have homelessness as a core business,” said Anderson. “It might be concerned about it, but when you talk about municipal core businesses, it might be more concerned with fire prevention or police protection.”

In Rock Island, Community and Economic Development director Jeff Eder said his city also qualifies for CDBG funds, which are largely used to fund economic development programs like the demolition of uninhabitable buildings.

“Sometimes we may spend a little more on demo than in other years, but from my staff standpoint, I can never have enough demolition money,” said Eder. “We have to prioritize that. When we’re demo-ing, it’s a danger to the public.”

Rock Island received nearly $932,000 in CDBG funds during this year. Eder said that out of the 15 percent allocated to public services like homelessness assistance, the Martin Luther King Center is one of the largest recipients of the funds. Just like in Moline, Eder and other city administrators believe that outside organizations have a better grip on the needs of the homeless that the city itself.

“It (homelessness) has come up in conversation,” said Eder. “We think there are other organizations that deal with that better than the city does, so we tend to support those organizations.”

In fact, Anderson said cities like Moline are only directly involved with those threatened by homelessness. This year, that city dedicated 95 percent of CDBG funds to investment in low to moderate income housing. HUD mandates that at least 70 percent must be dedicated to those investments. These funds help support programs like home repair grants. Individuals or families who, for example, might need a new roof or furnace to keep them in their home can apply for repair funds through that program. Anderson said this helps keep people from having to live on the street in the first place.

“One of the city’s philosophies has been maintaining neighborhood quality and keeping families in their homes,” said Anderson. “If they didn’t have that assistance, then they might be looking at having to leave their house.”

While residents can apply for these funds online or in person at city hall, they can expect to wait for nearly two years before they receive funding. Despite the long wait, Anderson reported that 40 to 100 households benefited from CDBG funds this year and cited high demand as the cause for the delays.

For now, the Quad City government stance on homelessness is to take a supporting role, using funds from grants like CDBG to make sure humanitarian agencies like Bethany Transitional Housing and Project NOW can provide services. Anderson said his department, like others in the Quad Cities, will continue to keep the lines of communication open with those organizations so every homeless person in the city can get the help they need.