‘The Information Age’ has been used to describe the recent past; networks of technology have made possible the internet, along with widespread dissemination of news and other data. These advancements represent a massive leap in the scale at which information can be shared and, as the amount of reliable information has grown, false information has become just as accessible. In other words, we have all almost certainly been exposed to mis- and disinformation. What effects might this exposure have on our beliefs and actions? What does your brain look like on fake facts?

To tackle these questions, it will be important to know how we become convinced of things in the first place. David Snowball teaches about mass persuasion as a professor in Augustana’s communication studies department, and founded a course called ‘Propaganda’. Though the topic may sound extreme, it can look as mundane as advertising. Snowball gives a vehicular example.

“80% of American vehicle sales are SUVs or light trucks; SUVs, historically, didn’t exist,” Snowball said. “They were a new product category, which kind of suggests that we don’t actually need them, but we were sold a need.”

In the case of advertising, Snowball pointed to the “first-rate” psychological research performed by companies hoping to sell us products. Larger and heavier vehicles, he said, have become America’s preference despite their associated environmental, financial and safety costs. This discrepancy points to the power of mass persuasion to overshadow concerns with feelings of need, conformity and pride.

“The course tends to start by getting people to think a little bit about what drives our beliefs and behaviors,” Snowball said. “How do you control the beliefs and behaviors of very large groups of people?”

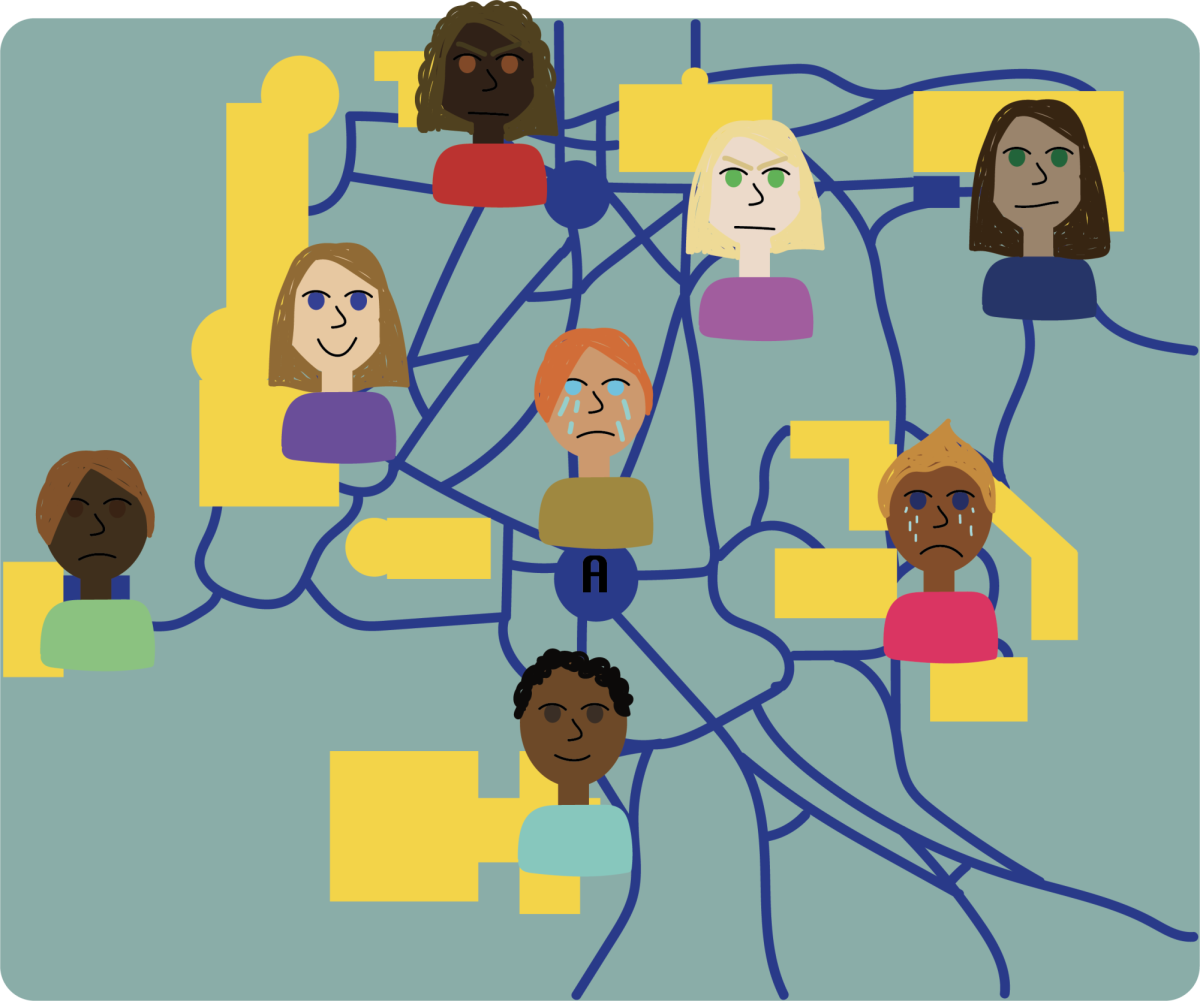

Think about the passage of information through different social groups. Odds are, each group will be receptive to slightly (even totally) different messages. Try inputting the same search term on different news websites or social media platforms to see how wildly conversations can differ. To get a foothold in these groups, interested parties must know their audience. What makes a group excited, scared or proud? What issues have they been interested in, and what needs can they be sold?

Those able to answer these questions can gain influence over beliefs and actions. Successful persuasion techniques, Snowball said, “come to you from people you trust [and] build on things you already believe.” They can drive people to otherize those they may have much in common with and act in ways that drive division rather than unity. It can be easy, then, to think of misinformation as strictly political and avoidable if one sticks to scientific thought. According to Kevin Geedey, an Augustana professor of biology and environmental studies, science media is not immune from the practices and biases of misinformation.

“World health organizations say that the healthiest amount of alcohol to consume is none, whereas when I was growing up, people would say a glass of wine a day might be good for you,” Geedey said. “It’s going to be tempting for somebody who enjoys an occasional drink to cherry-pick the studies that show what they want to be true.”

‘Cherry-picking’ is the name for one of many recognized logical fallacies, or common errors in thinking. Specifically, it describes the practice of choosing to only acknowledge or consume information which confirms or aligns with existing beliefs. In science, as new data provides new insights, this might look like only sticking to older findings. It might also look like ‘doing your own research’, a phrase which Geedey said has taken on a less-than-rigorous connotation.

“I can easily find YouTube videos that are going to support whatever opinion I want supported, rather than looking at a very careful scientific consensus that may not match my desires at all,” Geedey said.

Social and psychological factors drive the influence of misinformation, even when we think we’re being objective. This knowledge can make the information landscape appear bleak and impossible to traverse, but it also provides the foundation for defending against it. The first step can be as simple as asking questions about your community–What do your friends believe and why? What social or political issues are your neighbors concerned about? Snowball said that reversing a trend of isolation is vital in protecting information integrity.

“As our technologies have advanced, we have created the illusion that we need each other less and less,” Snowball said.

If community engagement seems inaccessible or daunting, Geedey recommends starting within smaller groups, like a circle of friends. As he put it, “have friends that are willing to say, ‘you’re talking nonsense right now.’”

Another strategy is to practice interroception, or the knowledge of one’s own physical and emotional state. For avid doomscrollers, media consumption might be paired with negative emotions and feelings of panic or danger, states which Snowball said make us vulnerable to misinformation.

“If you know that your date is coming through the door in five minutes and is expecting dinner, you don’t look at ten [food] options, you grab for one,” Snowball said. “If [you are] sufficiently frightened, you’re going to listen to fewer ideas, consider fewer possibilities and react predictably.”

Of course, the prevalence of misinformation and the complexity of media don’t mean that there is no good information available. Just as a plate of spaghetti might call for a specific tool; a fork, engaging in the media environment calls for the tool of media literacy. Although the idea may be widely familiar, media-literate practices might not be as clear.

Garrett Traylor works at Tredway Library as a research and instruction librarian. With a focus on arts and communication, their work demands the ability to understand and analyze media for academic projects, library outreach and student needs. They define the concept broadly, reflecting an understanding that information is everywhere.

“Media literacy is being able to understand the quality, scope, relevance, usefulness and truthfulness of information that you encounter, and that’s across so many different types of resources,” Traylor said.

Traylor’s recommendation is a strategy called lateral reading, or checking outside of one source to see what others say. If a claim is made on social media, find expert opinions from different peer-reviewed publications before reposting. Because misinformation can be quite profitable, they also suggest a follow-the-money approach to source vetting.

“What is the financial motivation for XYZ source to make such a claim?” Traylor said. ”You can sometimes trace who owns a source, or you can look at the types of ads that they run.”

This is not to say that one partisan ad or instance of biased wording disqualifies a piece of media or an entire source. Avoiding misinformation and unfounded beliefs can be as complex as forming and distributing them. There is a reason that propaganda plays on emotion and passive engagement and, if media literacy strategies sound tiring to implement, there’s a reason for that, too.

“Part of the exhaustion that people have to actually do fact checking, is that there’s already so much information overload,” Traylor said. “And the way to combat that is to look at more stuff?”

Traylor does not suggest that all media should be fact-checked, but instead that it should be consumed with an understanding of its characteristics.

“Being media literate does not mean you no longer watch Jersey Shore,” he said.

What it does mean is that Jersey Shore time is separate from news media time, which is separate from social media scrolling time. Partitioning these activities can directly combat information overload and exhaustion.

To follow Geedey or Snowball’s advice of checking and being checked through in-person social interaction, it is not necessary to call out every fallacy or flaw all the time. Similar to the enjoyment of watching Jersey Shore is the enjoyment of the irrational or the nonacademic. In other words, be kind and reasonable about what corrections you make.

“If you tell your neighbor, ‘you’re reading the horoscope; you shouldn’t do that,’ I think it would be reasonable for your neighbor to say, ‘why don’t you mind your business?’” Geedey said. “If your neighbor has incorrect beliefs about immigrants, maybe we have more of a duty to communicate and help folks make decisions based on real information.”

As generations continue to grow up with access to the internet, news media and ever-present advertising, the ability to differentiate fact from fiction and opinion remains as important as ever. Doing so may take not just fact-checking, but a commitment to our friends and communities and an understanding of our strengths and weaknesses.

“If you build systems on truth, they’re more resilient because you don’t have to make things up to make them work,” Traylor said.