How far would you travel to understand the heart of a community? For two Augustana College students, the answer was about 3,700 miles. Armed with a thirst for exploration and a grant from the Freistat Center for Studies in World Peace, Paige Meyer and Allison McPeak set out on a two-week journey to Northern Ireland. There, they unearthed the power, resilience and beauty of queer communities and the arts.

The project’s origins trace back to Meyer’s first year, after taking Dr. Adam Kaul’s introduction to anthropology class. Intrigued by Northern Ireland’s unique landscape, Meyer reached out to Kaul, who would join her on the trip. Meyer’s roommate, McPeak, was an equally enthusiastic participant with research plans of her own.

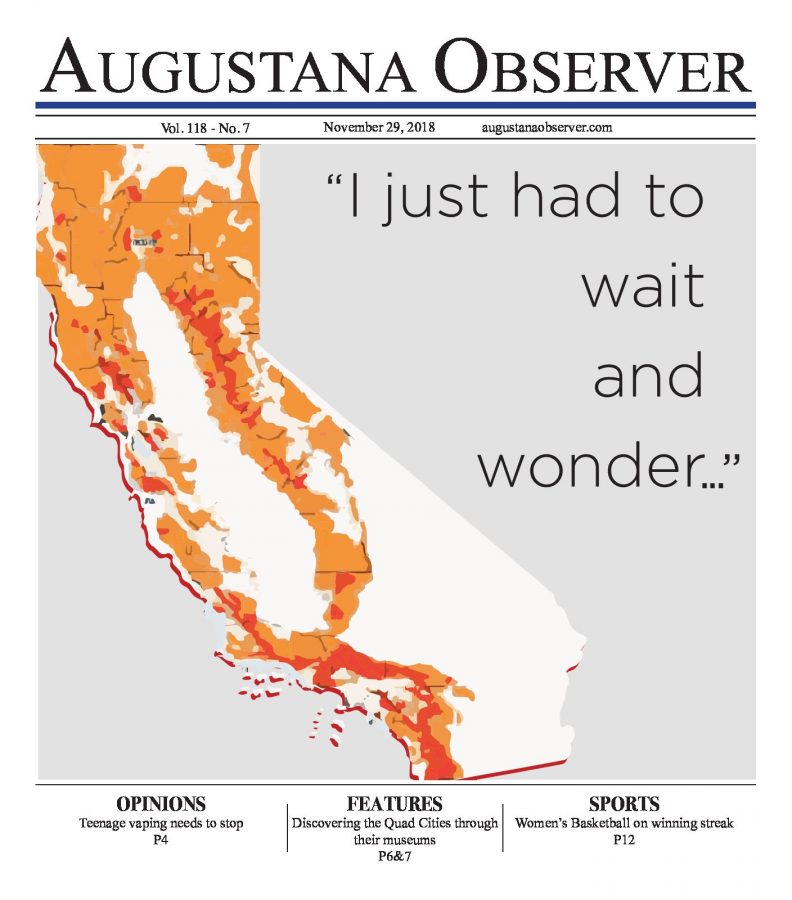

To understand the context of Meyer and McPeak’s research, it’s essential to look back at the recent history that continues to shape Northern Ireland today. The conflict, often referred to as ‘The Troubles,’ lasted from the late 1960s until the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. This period was marked by sectarian and political strife primarily between Catholic nationalists, who identified as Irish and sought a united Ireland, and Protestant unionists, who identified as British and wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom.

While religious identities became focal points, the conflict was deeply rooted in political and territorial disputes. Many Catholics faced discrimination in housing, employment, and political representation, fueling resentment against the unionist-dominated government. Civil rights movements in the 1960s sought to address these inequalities but were met with resistance, which escalated into violent clashes.

The Good Friday Agreement in 1998 marked a significant step toward peace, establishing shared power between unionists and nationalists. However, tensions remain to this day. In areas like Derry/Londonderry—a city whose name alone reflects the divided loyalties of its residents—historical grievances and unresolved issues keep the peace process delicate and challenging.

Amid this backdrop, Meyer and McPeak’s research offers a unique glimpse into the ways identity and art is being redefined in Northern Ireland, especially among communities who have often been sidelined in the national conversation.

“I specifically wanted to focus on queer joy and happiness within the queer community after the troubles,” Meyer said.

Meyer, a sociology, anthropology and women and gender studies major with a minor in political science, set out to explore the experiences of queer individuals in a society emerging from conflict. Through extensive interviews and discussions with community members, she learned of the tentative joy which arose after the agreement.

“It was kind of left at the door, and queer people were able to come together and celebrate their identity in that way without being, you know, held back by religious identities,” Meyer said.

Her exploration took her to the Cathedral Quarter, affectionately dubbed the ‘Rainbow Quarter.’ Despite the heavy political tensions in the area, she noted that the queer community was able to move into those spaces and create their own safe space there.

“During this time of political upheaval,” Meyer said, “the queer community moved into spaces that were often deemed dangerous, transforming them into havens of self-expression.”

That self-expression was palpable during an encounter Meyer had with a counter-protester at City Hall, where tensions between religious factions bubbled over. Standing defiantly with a pride flag, the man played queer music and show tunes, “trying to put a face to what everybody there was so scared of.”

While her research itself was thoroughly planned, Meyer came upon unexpected joys, like a queer set dancing lesson led by Alexa Moore of the Rainbow Project.

“It was my favorite part of the entire trip,” Meyer said.

The session allowed her to connect with locals, one of whom, upon seeing Meyer and her peers, asked, “Why are you coming to Northern Ireland when there’s nothing that happens here?” This charming exchange highlighted a contrast: while the individual perceived Belfast as uneventful, the research team witnessed a city alive with culture.

Navigating cultural sensitivity proved essential, especially during an Orange Order Parade, a significant event rooted in the region’s Protestant history. Engaging with parade-goers, Meyer found herself in a delicate conversation about the divided history encapsulated in the names “Derry” and “Londonderry.” The complexities of identity and nomenclature became a lens through which to view the ongoing religious conflict. In Meyer’s research, dialogue was vital.

“What I ended up saying was, ‘We went to Derry/Londonderry,’ because usually if you’re Protestant, [it’s]’ Londonderry’, and if you’re Catholic, [it’s] ‘Derry,’” Meyer said.

While logistical challenges arose—like navigating cash-only cabs and timed interviews—they were mitigated by guidance from Kaul, whose own research has led him to spend decades in and out of Ireland. Ultimately, Meyer’s research yielded six hours of interviews. In examining the similarities and differences between the queer communities in Belfast and her own in the Quad Cities, Meyer saw a common thread.

“A large part of the queer community is student-based, which is quite similar to Rock Island,” Meyer said.

McPeak, an English and Theater Arts major, simultaneously investigated the role of the arts in bridging political divides. Her research focused on three central questions: How do the arts work to bridge gaps between political groups? How do underrepresented demographics express themselves through the theater arts? What does theater look like on a highly political stage?

Her research examined how artistic expression might foster collaboration across conflicting beliefs. As a theater major, McPeak was passionate about understanding the role of the arts in driving social change. She discovered that they often serve as a space for people to come together and create something positive, which resonated with her own career goals.

“I was excited by the opportunity to explore how the arts can be a tool for peace,” McPeak said. “In Northern Ireland, theater isn’t just a form of entertainment—it’s a space where people can come together and create something positive.”

Visiting the Free Derry Museum, she encountered stories of loss and resilience that grounded her research in real-world experiences. She approached interviews carefully to ensure she was respectful while gathering data.

“It was very emotional for me, and it helped me contextualize my research in a meaningful way,” McPeak said. “It was important to ask questions that could guide us toward understanding the experience without directly confronting people about their political beliefs.”

During his time accompanying Meyer and McPeak, Kaul saw both students take ownership of their research as they engaged with peace studies, arts and advocacy.

“The students took the initiative,” Kaul said, “and I was there to guide, encourage and support them as they asked the questions that mattered.”

Though their questions were valuable, they didn’t pay for plane tickets on their own. Besides the students’ own initiative, one Augustana institution made their trip possible: The William F. Freistat Center, known for its focus on peace and justice studies.

Upon learning that the Freistat Center could provide a research grant, McPeak was drawn to apply. The center specifically supports peace and justice research—a field that hadn’t felt accessible before.

“It was really exciting to me because I had never seen research opportunities like this for students in the humanities. It was directly affiliated with Augustana,” McPeak said.

For Meyer and McPeak, the grant was instrumental in affording them the freedom to conduct immersive research, and their findings from Northern Ireland have contributed to broader conversations about queer community resilience and advocacy. Back on campus, they presented their research during Augustana’s Symposium Day, drawing connections to the experiences of queer individuals in the U.S. and the Quad Cities area.

Heidi Storl, chair of the Freistat Center, shared her enthusiasm for the grant, emphasizing the importance of research that promotes understanding and serves marginalized groups.

“Entering a culture with significant historical challenges and exploring sensitive issues, as Allison and Paige did, is remarkably brave,” Storl said. “Their research sheds light on the resilience of the LGBTQ+ community in a context of division and highlights universal human connections.”

With their research, Paige Meyer and Allison McPeak have not only mapped the intersections of queer belonging and art in Northern Ireland but have also illuminated pathways for understanding and solidarity that transcend borders. Their research is a testament to the power of inquiry and the importance of voices that, when heard, can weave together a richer narrative of humanity.