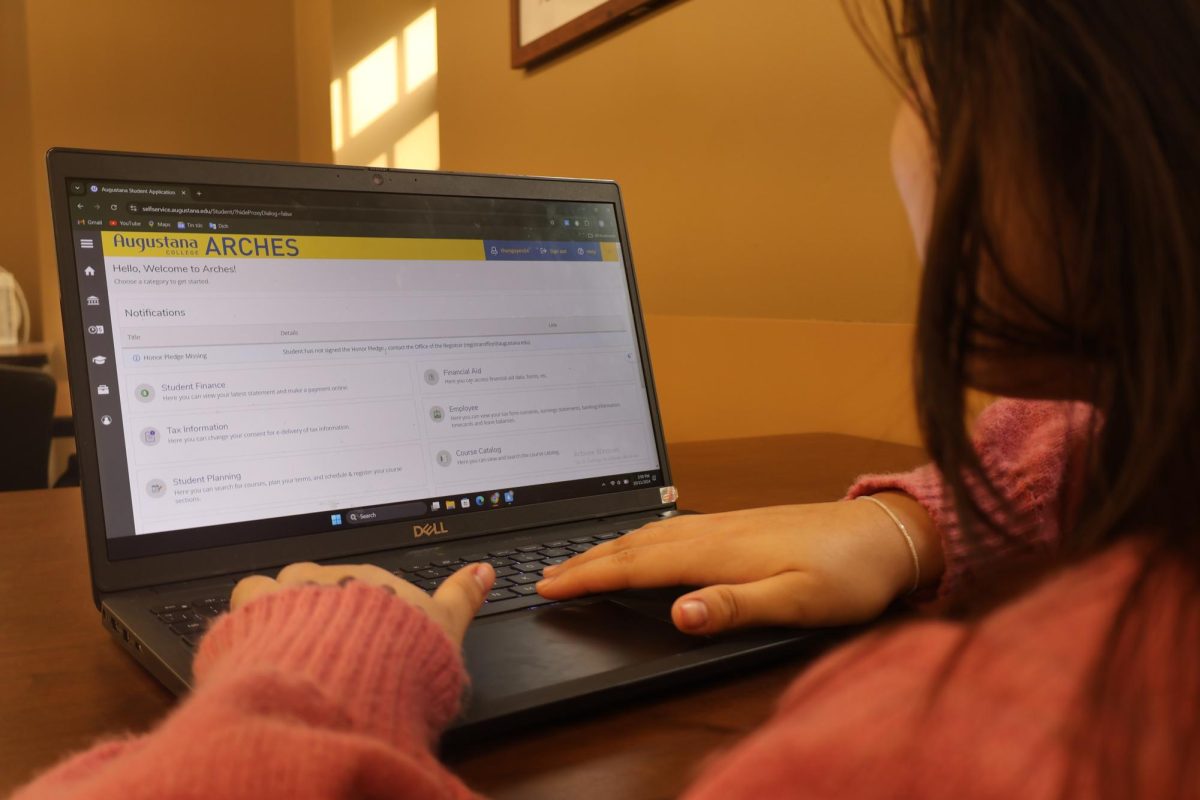

Each year, Augustana’s First-Year students have the opportunity to submit their research to the Tredway Library Prize for First-Year Research. This competition presents an opportunity to celebrate Augie’s First-Year students and to hold campus-wide conversations about student issues of interest. This year’s winner, Ethan Gabrys, researched a topic becoming more and more relevant to students today: artificial intelligence (AI). Gabrys’ essay focused on AI art software and asked questions about ethics, philosophy and ownership.

Gabrys’ research was inspired by a course he took as part of his First Year Honors (FYH) sequence. That course, taught by Augustana philosophy lecturer Deke Gould, was all about transhumanism. Gould said that transhumanism has implications for human technology use.

“The transhumanism topic is related to a cultural movement which began getting a lot more attention in the 1960s in California,” Gould said. “Transhumanism might be defined as the thesis that if humans can enhance themselves, they should.”

The promotion of human enhancement mirrors the larger conversation regarding AI art tools. Created to produce visual designs of a requested style and content in seconds, these tools could be argued as enhancements to human thought and creation. At the same time, there is pushback against the idea of AI as a creative force. Gould said that the concept of improving on the human body and mind already shows up in day-to-day life.

“One of the questions I like to investigate in this class is, ‘Are we already in a sense enhanced, given that, for example, all of us here in this community are vaccinated?’ There’s a sense in which our immune systems are enhanced by technology,” Gould said.

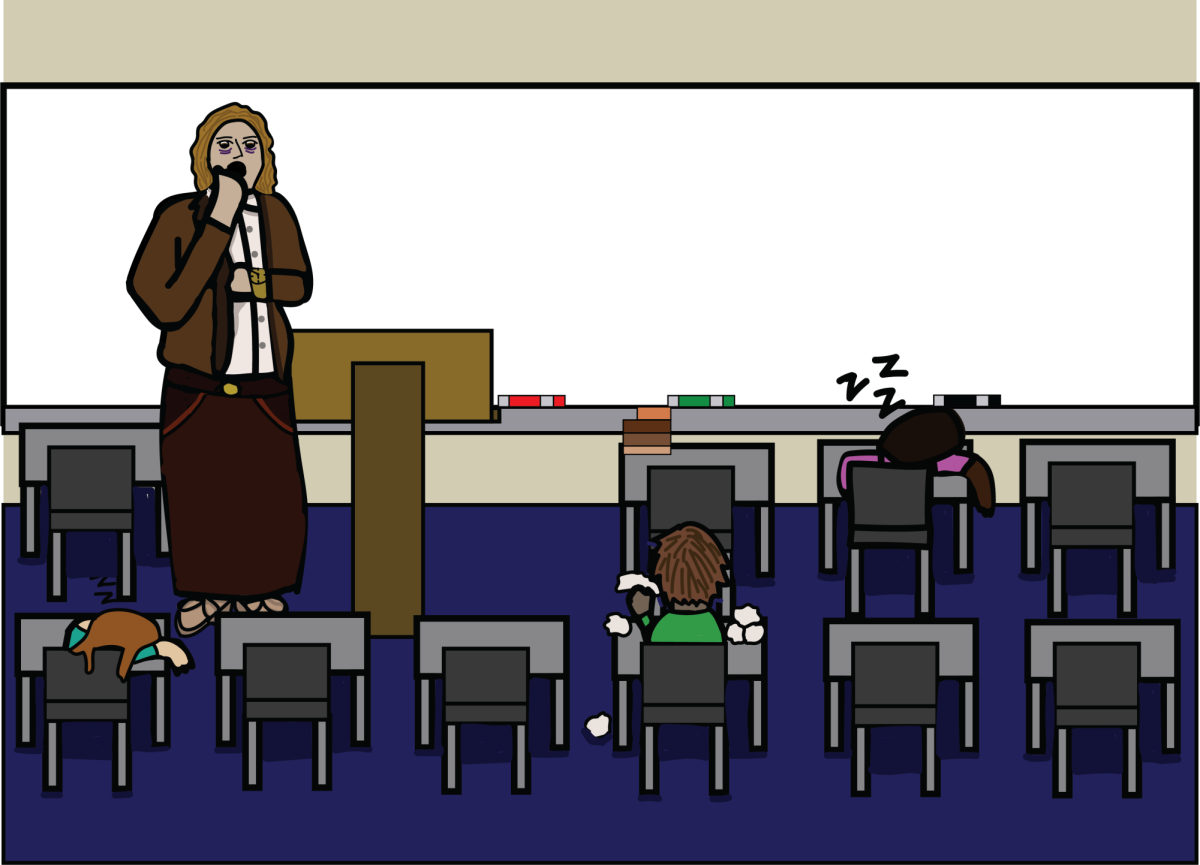

In Gabrys’ research, he explores the development and use of AI art tools. Motivated by a shift in public sentiment as well as a rapid increase in the actual use of these tools, he asks what effects we might not be considering. Gabrys said that past sentiments have downplayed the impact of AI text and image creation tools on the arts.

“When AI itself was first starting to become a thing, people were saying, ‘That stuff is for humans. Technology can’t do that. It’s going to replace manual labor,’ but as we’re seeing it evolve, AI is being used for chatbots, creating text, AI art and deepfake videos,” Gabrys said.

Even when AI is utilized as an idea-generation tool, the way that the software is developed can present ethical challenges to its use. Though AI art tools are described as “generative,” they are invariably trained on the unpaid work of human creators. In this sense, what do they really generate?

“Almost every AI art software was trained using other people’s art. It’s impossible to use [them] without having the influence of other people within them,” Gabrys said.

One of the most enduring questions about technology is that of dissemination. Once technology becomes widely available, it cannot easily be taken back should a problem of safety or ethics arise. Different solutions exist, from merging with technology in favor of its benefits to intensely regulating the growing AI software market, but each presents its own set of challenges.

In practice, the solution of a human-technology merger might take the form of universal acceptance of the use of AI tools or a less human-centered approach to intellectual property and content ownership. Regulation might look like oversight of the training process or requirements to obtain consent from the artists who train the model.

“The problem is, it’s really hard to see exactly where to pin the blame or praise, because so much of what we do is the product of lots of the work of lots and lots of people,” Gould said.

The market and a desire for quick, creative tools exercises influence on the development and use of AI art tools. Senior Esme O’Rourke, who studies graphic design and studio art at Augustana, said that she’s experimented with the use of AI tools in the workplace.

“When I was an intern at a design firm this past summer, we started to dip our toes into how we were going to use AI to save us time and money and resources,” O’Rourke said.

“For example, if I had illustrated a wide landscape for product packaging but the length of the painting needed to be longer or wider, I could ask AI to add on to my painting.”

Companies often turn to the tools which are the cheapest, easiest to implement and require the least employee training. As compared to the training, salary and materials costs associated with hiring an artist to expand an illustration, requesting the change from AI art software may only be associated with a subscription fee.

The rich conversation regarding the use of AI art tools and what it means to be human is part of the reason why Gabrys was selected as this year’s winner. Research and Instruction Librarians Garrett Traylor and Kaitlyn Goss-Peirce were judges for this year’s prize, faced with the difficult task of choosing one piece of research out of a varied and talented field. Goss-Peirce said that there are different measures to ensure a fair competition.

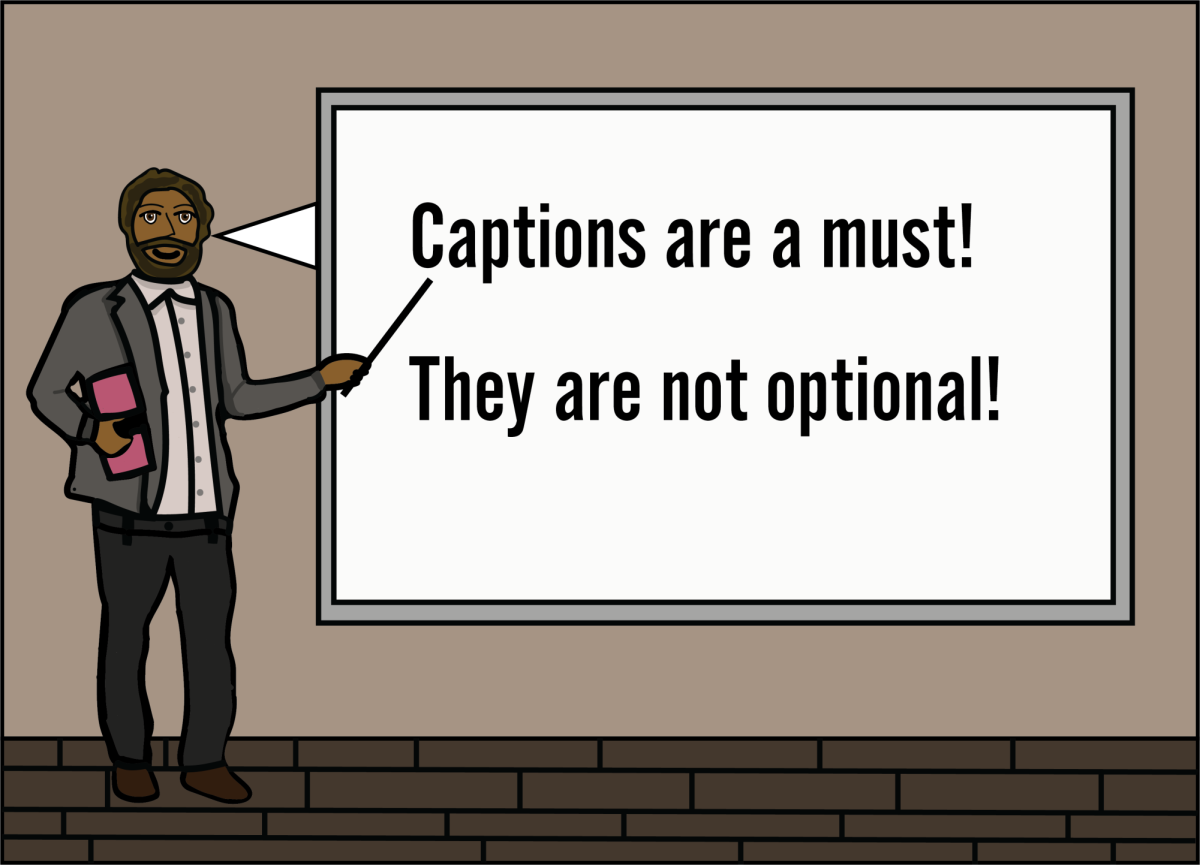

“We have a very loose rubric to give some structure to what we look for,” Goss-Peirce said. “How scaffolded is the research throughout the paper? Are they actually engaging with the researcher in addition to listing details? Do they have a diverse set of resources that they’re pulling from, or are they only using one type of resource or perspective?”

Asking broad questions like this allows for a more objective analysis of each piece of research submitted. Because of the double-blinded nature of the judging process, students are encouraged to engage with library resources, including the expertise of research librarians and other staff.

“We want it to be a well rounded piece of writing as well as a well rounded research project,”

Traylor said. “The librarians are some of our library resources. We’re here to help people; I think this year’s contest winner had some consultation sessions to build up their research.”

Gabrys’ research touches on a contemporary topic and its relevance to students. It asks difficult questions about what it means to create, to use AI and to be human. Much like AI art itself, the research is an act of collaboration. As students navigate their education with the increased availability of AI tools, it is vital to consider their ethics and their utility.

“AI is only going to get more and more intense,” O’Rourke said. “Right now it’s kind of like the wild west with AI. There are no rules, so I definitely think it’s something to talk about.”

Traylor said that students should consider what AI provides but also what it might take away.

“Voice can be replicated by AI. What does that mean for finding your voice? What does that mean for your expression as students, learners, people and citizens?”

Ethan Gabrys is a former employee of the Observer.