Why the African American read-in continues to be important

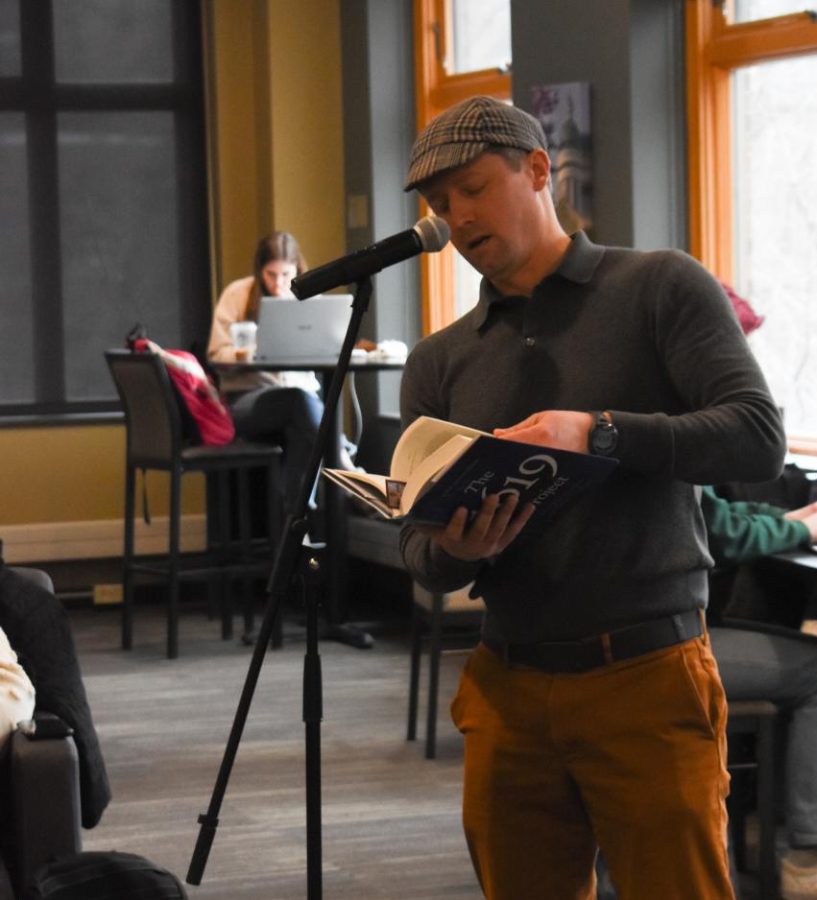

English Language Learner Specialist Jacob M. Romaniello reads to Augie students at the Brew as part of the African American Read-In on Thursday, Feb. 24, 2022.

March 4, 2022

February is Black History Month and many different offices, clubs and organizations on campus plan events and activities to celebrate different African American voices.

One of the ways the Reading Writing Center (RWC) celebrates African American history is by holding its annual African American Read-In. This year, the event took place Thursday, Feb. 24, and was put together by the RWC’s diversity task force and supported by the National Council of Teachers of English.

At the Read-In, students and faculty came to the brew and read different works by African American authors aloud.

The African American Read-In gave a platform to students who wanted to come up and read something they found important, interesting or something they liked by an African American author. Students from all races and ethnic backgrounds went up to speak.

Junior Gavinya Wijesekera is a student member of the RWC Diversity task force. “We want to recognize that higher education was initially made without people of color in mind,” Wijesekera said.

For many years, only white men and women were allowed to seek higher education. It wasn’t until the late 1900s when African Americans were finally allowed to seek higher education at colleges and universities. In 1963, president John F. Kennedy had to deploy the National Guard, forcing the University of Alabama to desegregate and let African American students in. This happened less than 100 years ago.

“The RWC wants to make sure that we create spaces for people of color and we are made for people of color in mind,” Wijesekera said.

Creating spaces for people of color to speak and express themselves is very important. Every voice counts, especially when some voices have been silenced for many generations. It is just as important that we understand that academia is not just for middle to high-class white men and women. It is for all people of all races and classes who are looking to gain more knowledge about the world around them.

“The American educational system has not put Black authors in the forefront at all,” Dr. Sharon Varallo, one of the performers at the African American Read-In, said. “And it’s high time that that changes.”

Right now, very few English class curricula contain literature by African American authors. A majority of the time, you have to take a special class that specifically focuses on African American authors. The Read-In and those who participate want to bring African American voices into the classroom.

At the Read-In, students and faculty read from a myriad of African American authors. Dr. Jacob Romaneillo read pieces from authors Hanif Abdurraqib, Nikole Hannah-Jones and Wesley Morris. “What’s been written sometimes is very critical of power structures and is pushing, resisting, abolishing institutional racism and those sorts of things. To read that in a public space is very brave too,” Romanello said.

Varallo has performed at the African American Read-In in past years. This year, she wanted to do something different from last year.Varallo performed pieces by Jesmyn Ward, Isabel Wilkerson and Natasha Trethewey. “I really just loved the continuity of these pieces,” Varallo said.

Dr. Lucas Street, director of the RWC and one of the people to help organize the African American Read-In, said that “when the students, our students read those pieces or faculty for that matter, it just brings out even more richness. You get to hear a little bit of that reader’s personality and why the piece they chose is important to them.”

Not only was the sign-up list of readers for the African American Read-In full, but there were also people who decided to give impromptu performances.

“We were so worried that no one was going to sign up, and last night we were on the Google document and all the slots were full,” Wijesekera said. “It was seeing people just rise to the occasion.”

The Read-In is a tradition the RWC will carry on for years to come. “We see ourselves as an actively anti-racist space,” Street said. “We are always trying to promote and uphold marginalized voices.”

If you want to read and support amazing African American writers, Romaniello recommends “They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us” by Hanif Abdurraqib and “The 1619 Project” by Nikole Hannah-Jones and Wesley Morris. You can also stop by the RWC and look at one of their walls, as they have a list of books by African American authors recommended by some of the tutors.

“Celebrating Black art and Black voices is important,” Wijesekera said.