Misty Urban, author of “The Necessaries,” is reading from the “Canterbury Tales” to a crowded hall in the Rock Island Public Library (RIPL). In Middle English, she shares the retraction added by Geoffrey Chaucer himself, which she explains could be a plea by Chaucer for his audience to forgive his sexually explicit works. What is remarkable, however, is the way Chaucer lists these very works, advertising them and almost daring the reader to judge him themselves. “If you ever want to talk to someone about a banned book, pick Chaucer,” Urban said. “He’s canonical because of the breadth of his work; they hold worlds within them.”

The “Canterbury Tales” was just one of many works that have faced censorship and criticism since their publication. At RIPL’s Banned Book Week celebration on Wednesday, Sept. 26, eight more of these books were discussed by local writers and reading enthusiasts. The readings were accompanied by food and free giveaways.

Three Augustana first-year students, Trang Hoang, Hope Wells and Ryan Sackfield, were in attendance. Banned Books Week was also celebrated at Augustana. An informational display in the Thomas Tredway Library was coordinated by research and instruction librarian Maria Emerson, and Augustana literary society Unabridged held a discussion on Tuesday, Sept. 25.

Banned Books Week began in 1982 in response to a wave of protests and challenges to certain books in schools and libraries. The American Library Association (ALA), the American Booksellers Association and the National Association of College Stores organized the first celebration; this year’s celebration ran from Sept. 23-29.

Ryan Collins, executive director of the Midwest Writing Center that helped organize the RIPL event, read from both William. S. Burroughs’ “Academy 23” and Part 3 of Alan Ginsberg’s “Howl.”

“Book banning drums up interest in books that people wouldn’t normally read,” Collins said prior to the readings. “And that’s a good thing, because author sales and readership automatically rise.”

“There are so many books people wouldn’t even know about if there hadn’t been a challenge to them,” Emily Tobin, young adult librarian at RIPL, said. “And some of those are classics of the 20th century, which have themes that are still relevant to us today.”

Some of the books read at the event had been banned for reasons which were perhaps predictable. Claire Kovacs, director of the Augustana Teaching Museum of Art, read from Erica Jong’s “The Fear of Flying,” criticized for its frank portrayal of female sexuality and desire. John Hagar read from Karl Marx’s “Communist Manifesto.” Lauren Wood, owner of Paradisiac Publishing, read from Bret Easton Ellis’ “American Psycho,” which is narrated by a serial killer. Lisa Lockheart, RIPL’s publicity liaison, read from Philip Pullman’s “The Golden Compass,” which was challenged on religious grounds. She pointed out that the title of its parent trilogy, “His Dark Materials,” was borrowed from John Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” also a banned work.

“The goal of Banned Books Week is that people have to realize they decide what to read. That’s something that’s unique to our country,” Lockheart said prior to the event. “A good library will have something that offends someone. But it’s a core value of libraries to celebrate the freedom to read.”

Nevertheless, the controversy around some books is less cut and dry.

Jodie Toohey, Midwest Writing Center president, read a chapter from one of the “Little House on the Prairie” books by Laura Ingalls Wilder. In 2018, the American Library Association removed Wilder’s name from a children’s literature award because of what Toohey described as the “anti-Native American and anti-black sentiments” in her books. However, Toohey said she was reading from the series because it was a valuable depiction of frontier life. “What do we gain by denying our past?” she asked the audience.

Members of Unabridged also discussed the question of whether racially and ethnically insensitive books – which are nonetheless important classical and historical canon – should be banned.

Sophomore Tamara Day, who attended the meeting, said that such books were a unique part of the historical record. “It’s not like we can go back to that time period and see for ourselves what happened,” Day said, to general agreement.

Maria Emerson also shared this opinion. “We need to recognize history and what happened in the past. Ignoring that won’t solve anything,” she said.

Asked whether books with politically incorrect and harmful ideas should remain in circulation, Angela Campbell, RIPL director, said, “Those ideas are already out in the world. But it’s our choice to decide whether to follow them, and you have to read to figure that out.”

To general applause and laughter, Campbell read a children’s picture book by John Oliver, titled “A Day in The Life Of Marlon Bundo,” parodying a picture book released by Vice President Mike Pence’s family earlier this year. The book appears to portray Mike Pence as a “stink bug” and satirizes his views on LGBTQ rights.

Another banned children’s book, “And Tango Makes Three” by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson, was read at the Unabridged meeting. The book features two male penguins who fall in love and start a family together. Alex Bernheimer and Katie Oestmann, Unabridged president and vice president, respectively, encouraged other members to discuss whether books like this were banned because they featured homosexuality, or whether they introduced sexuality to children at a young age. The conversation then turned to whether librarians should regulate children’s reading material.

“So many kids lead lives that we wouldn’t let them read about,” Emily Tobin said. “The books they read should reflect their lives in some way, I think. Books like ‘The Hate U Give’ and ‘All American Boy,’ which discuss police brutality – well, you can’t pretend that’s not real, because the kids have been through that.”

The last reading of the evening was by John Turner of Southeastern Community College, Iowa, and Monica Flink; they performed a passage from Jenny Lawson’s “Furiously Happy.”

A common theme of discussion was whether current opposition at the highest levels of government to free speech and freedom of the press would spill over into the literary world. “I don’t think anything’s really impossible at this point, unfortunately,” Emerson said. “I think that when people are uncomfortable with something, they try as much as they can to stop it from happening, by silencing those voices or pretending it doesn’t happen.” She pointed out that over 50 percent of banned books deal with a “diverse” theme, such as LGBTQ issues, gender diversity, characters that are minorities or marginalized, people with disabilities or mental illness.

“The mindset of sticking to what you know is dangerous, because you want to learn about other people’s lived experience.” Emerson continued, “And that can carry over into books. People don’t want to recognize the ongoing problems; it’s just easier to bury their heads in the sand.”

“Banned Books Week is my favorite holiday, but I’ve never felt as threatened as I do in recent times,” Campbell shared prior to her reading.

“I’ve been seeing a lot of Harrison Bergeron,” said former librarian Melanie Hanson of Davenport, referring to Kurt Vonnegut’s dystopian short story published in 1961. “There’s this idea of anti-intellectualism. It’s not cool to seek knowledge. People who want to know things are ridiculed. But we have access to more information than ever before, and it’s up to the reader now to identify what’s valid. So yeah, screw censorship.”

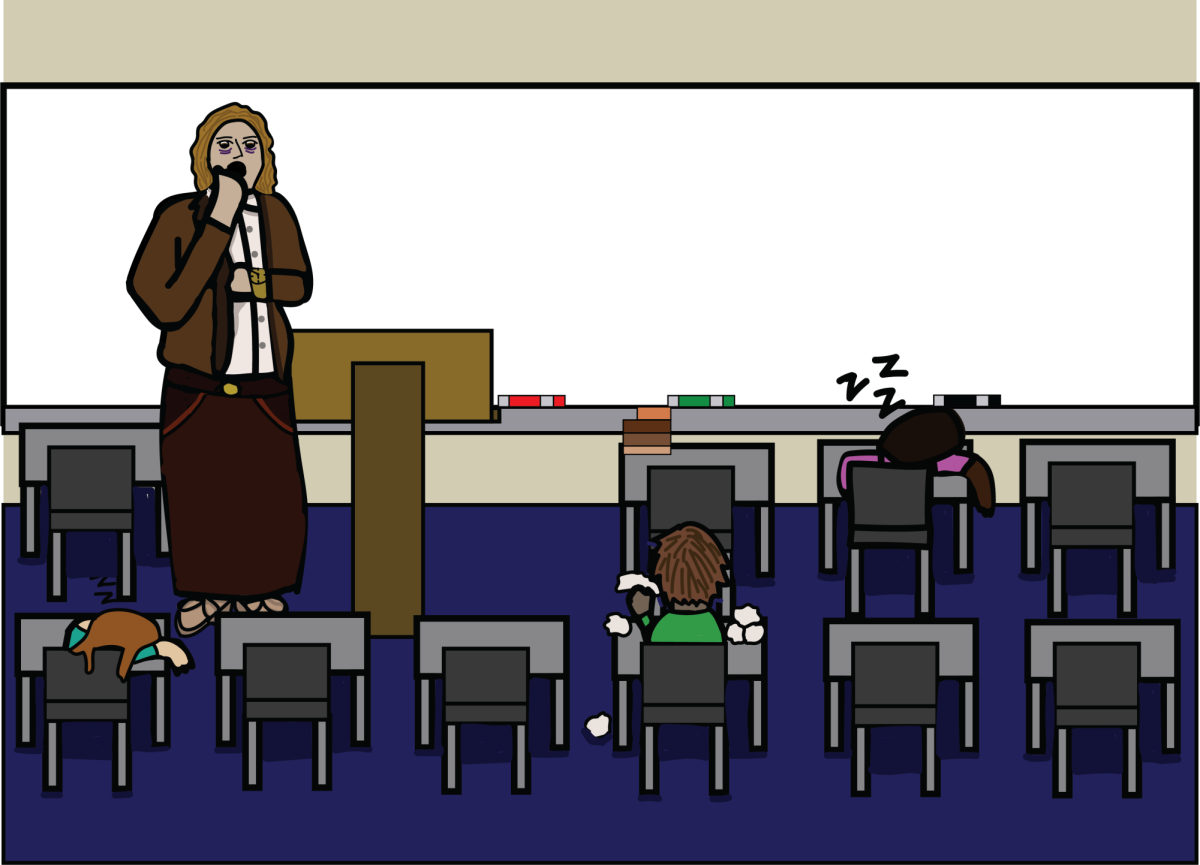

Photo Above: Sophomore Alex Bernheimer discusses banned books with the club. Photo by Christina Rossetti.

Categories:

Banned Books Week in the QC

October 4, 2018

0

More to Discover